|

| One of the re-creations of the Battle of Largs [source] |

Stormy weather struck the Norwegian fleet on the night of 30 September 1263; the next morning (1 October) found several ships driven aground on the Scottish mainland. Scottish archers found them and started shooting at the crews. The Norwegians rallied and fought back, reinforced with more men from other ships; joined by King Haakon, they camped ashore for the night.

On 2 October, Alexander's forces arrived and the Battle of Largs began. Although there is a brief mention in the Chronicle of Melrose and more detail in Hakonar saga Hakonarsonar ["The Saga of Hakon Hakonarson"] by Snorri Sturluson, it is impossible to know exactly how many men were on each side and how the battle was fought. Local records show that the Earl of Menteith maintained 120 sergeants, which gives a clue to how many soldiers might come from an area. The Saga says Haakon, with a force of 700+ men, stayed on the beach while about 200 men took the high ground a short way inland.

Supposedly, Alexander's approach prompted the men on the high ground to descend, fearing that they would be cut off from the main Norwegian force. Their hasty rush down from the high ground looked like a necessary retreat to the Norwegians on the beach, and they fled to their ships. In the chaos of the retreat, they took heavy casualties from the Scottish, who used cavalry with armored horses, archers, and some form of catapult.

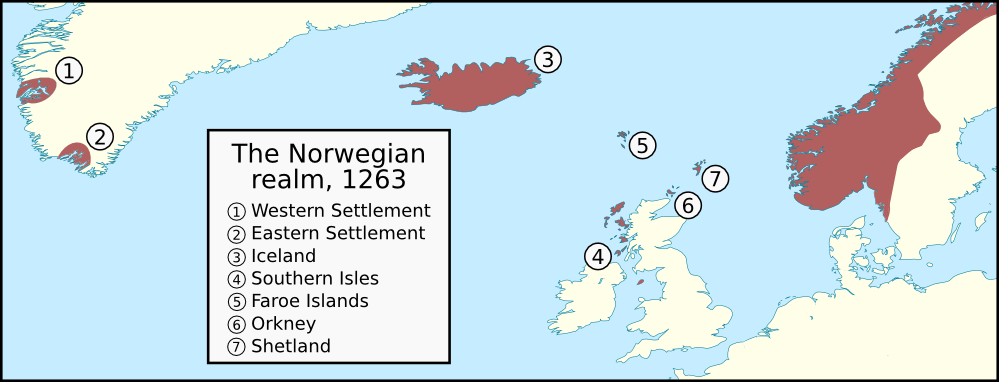

The Norwegians returned to collect their dead; Alexander allowed them. They then sailed to the Hebrides and later to Orkney, where Haakon died in December (he was 59 years old). Negotiations between Alexander and the Norwegians over the disputed territories continued, but slowly. Alexander built up his forces on land while Hakon's fleet suffered over the winter. Although the Battle of Largs was not decisive in any way, ultimately the aftermath led to a wearing down of Norwegian morale. In 1266, the Treaty of Perth created peace between the two countries, and gave the Hebrides and the Isle of Mann back to Scotland.