Unlike the modern book store, however, you had choices that are not available today. Once you had determined that he did have access to a copy of the book you wanted, you had to decide on certain features.

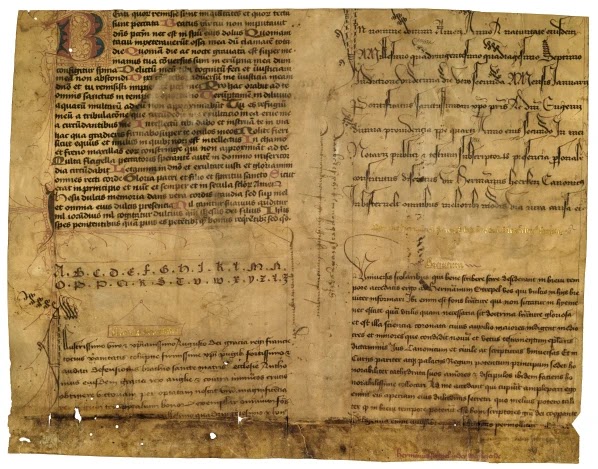

Did you want parchment or paper? What quality of parchment (were holes okay)? What script did you want it produced with? Did you want illustrations? Since it was being made from scratch for you, you had options we cannot (and, fortunately, do not have to) imagine today. I've made the illustration a little larger than usual (I hope it shows clearly in your browser), so that you can see not only the samples of script being advertised by a 15th century bookseller, but also the names of the different scripts written above each sample in gold lettering. This is an advertising sheet produced by professional scribe Herman Strepel of Münster in 1447.

And if you were producing the book and looking for more business, why not include ads for your services? A Paris manuscript includes, on the last page, “If someone else would like such a handsome book, come and look me up in Paris, across from the Notre Dame cathedral.”

Not every "addition" to a book was an ad. A Middle Dutch chronicle includes the line “For so little money I never want to produce a book ever again!”

Book production employed different skilled tradesmen: the scribe himself, the illustrator, and the person who did the binding of the completed pages. Inks and paper or parchment had to be readily available, so those manufacturers were kept busy by demand, especially in university towns. In Paris, the Rue St. Jacques was where you'd find the producers of Latin textbooks, making it easy for students to know where to go to order needed materials for study. A lot more about medieval books is available on this blog.

Of course Gutenberg changed a lot of that, which is why I consider his innovation to be one of the markers that the Medieval period had truly ended. Gutenberg's press did not end the need for something on which to put the printed word, however. Next I'll talk about the production of parchment.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.