The history of witchcraft, like any historical phenomenon, is a combination of truths, falsehoods, reinterpretations, and misunderstandings. What we now call "witchcraft" was defined differently by different groups—or rather,

what it was remained the same, but its

significance was redefined. I'll try to explain.

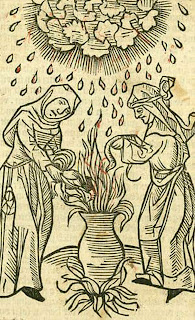

By the end of Charlemagne's reign in 814, overt paganism had died out in Western Europe, replaced by Christian practices. There were traditions that did not die out, however. Some examples are divination for the gender of an unborn child and dowsing for water; the mixing of substances intended to bring about an emotional effect such as love or desire; or attempts at healing illness using sympathetic magic (described here being used by a midwife).

"Magic" was sometimes a professional's pursuit. People like Ficino and Fibonacci and Geert Groote and even Hildegard of Bingen were associated with learning or practicing magic. There was a point in time, however, where these "un"natural practices were declared to be bad. That may well have started with Pope John XXII, when he declared such things to be heresy. This created the formal framework for investigating and prosecuting anyone suspected of practicing witchcraft by the Inquisition. This was in the 1320s. Now the woman in the village to whom you turned for medical or magical aid was suspect, and associating with her made you suspect.

What exactly constituted witchcraft and was worthy of accusation fluctuated with time and temperament. The 1487 Malleus Maleficarum ("Hammer of the Witches") became the manual for identifying the offenses of witches, which could be categorized in three levels:

“i) slight (ii) great, and (iii) very great.”

Slight offenses constitute something as simple as small groups meeting secretly in order to practice the craft, whereas very great, or violent, offenses included respecting and admiring heretics. With such a broad spectrum of infractions, accusing anyone of practicing the craft was possible. This, in conjunction with the broad spectrum of who could be a witch, pushed the witch craze to its apex. [source]

(The "craze" reached a peak in 17th century New England, when a husband and wife accused each other of witchcraft after the death of their child. It went to trial.)

The Malleus Maleficarum supported and extended John XXII's bull making witchcraft equal heresy. It firmly linked witchcraft to worship of the devil, and a thing to be avoided at all costs. Between 1450 and 1750, there were an estimated 110,000 trials for witchcraft, about half of which led to capital punishment.

It is times like this that I cannot help thinking of C.S. Lewis' words at the beginning of Mere Christianity:

Three hundred years ago people in England were putting witches to death. Was that what you call the 'Rule of Human Nature or Right Conduct?’ But surely the reason we do not execute witches is that we do not believe there are such things. If we did—if we really thought that there were people going about who had sold themselves to the devil and received supernatural powers from him in return and were using these powers to kill their neighbours or drive them mad or bring bad weather—surely we would all agree that if anyone deserved the death penalty, then these filthy quislings did?

He knows full well that witchcraft is not a thing to be condemned, and that it is arrogant of the modern age to look back and condemn the accusers of being stupid; they had no choice—if they truly believed what they were told—that they were acting to save themselves and their neighbors. It was a dark period in the human history of belief and fear of "The Other," which manifests itself in many ways, such as in this recent post.

Let us look at a specific witch trial in more detail, of a wealthy Kilkenny woman who was accused of witchcraft by her (perhaps less-than-neutral in this matter) stepchildren. See you tomorrow.