|

| Paul the Deacon |

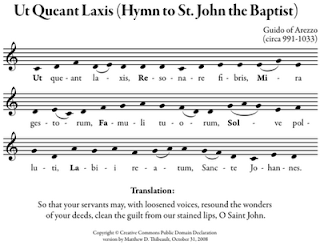

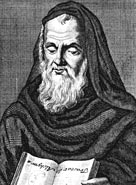

Ut queant laxis resonāre fibrisWhat does this have to do with Julie Andrews? Nothing, until the 11th century, when Guido of Arezzo (c.992-1050) proposed an ascending diatonic scale for music.* He realized that the hymn was a perfect mnemonic for the scale, and so he described the scale using the syllables on which the ascending tones fell: ut, re, mi, fa, sol, la. Around 1600, in Italy, a musicologist named Giovanni Battista Doni refined the scale by changing "ut" to "do" because he preferred the open vowel sound it created, and added a seventh note which he called "si" because of the SI initials from "Sancte Iohannes." So we had do re mi fa sol la si.

Mi ra gestorum famuli tuorum,

Sol ve polluti labii reatum,

Sancte Iohannes.

So that your servants may,

with loosened voices,

resound the wonders of your deeds,

clean the guilt from our stained lips, O Saint John!

It was a long time later that a Norwich, England music teacher named Sarah Glover (1785-1867) developed a method she called Sol-fa for teaching a capella singing, and changed si to ti so that each syllable would start with a different consonant sound.

Glover published her ideas, and they were further refined (and sometimes independently developed) by people like John Curwen, Pierre Galin, Aimé Paris, Emile Chevé. I cannot draw a direct line from any of these to Rodgers and Hammerstein, but by the time R&H came along, "singing the scales" was a commonplace way of teaching the rudiments of music to children. When R&H needed a number for a scene in the 1959 musical "The Sound of Music" when Maria teaches the children to sing—after discovering they knew nothing of singing because their father had forbidden it—what was more natural than using the sung scales that had been developed over the past thousand years? Hammerstein turned each note to a homonym to flesh out the lyrics, and the rest is theatrical/cinematic history.

Hammerstein should be grateful that he didn't have to write a lyric for "ut."

*"Ascending" is important here: previously, the scale was described as a series of descending notes.