09 November 2024

Louis, Eleanor, Annulment

05 November 2024

King Louis VII

Louis' childhood education was designed to prepare him for a high ecclesiastical position. He spent a lot of his youth therefore at Saint-Denis with the Abbot Suger, his father's advisor, which had the effect of making him a very devout Christian his whole life. The accidental death of Louis' older brother Philip in 1131 changed Louis' life forever. He was named heir apparent and anointed king by Pope Innocent II at Reims Cathedral. (The French Capetian dynasty for a time followed the practice of actually naming the heir as king while the father lived; see another example here.)

In 1137, Duke William X of Aquitaine died on a pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela. William had asked Louis VII to be his daughter Eleanor's guardian, and Louis VI moved quickly to have his son marry her, especially since she inherited her father's lands. Louis married Eleanor of Aquitaine that same year when he was 17 and she was a few years younger. As heir to the enormous province of Aquitaine, she was one of the wealthiest women in Europe; the alliance spread the Capetian territory significantly.

Louis VII died one week after the wedding, and all at once Louis and his new bride became King and Queen of France. Suddenly the raised-to-be-a-cleric Louis had the weight of running a kingdom on his shoulders, and his lively young and wealthy bride was not quite suited to the serious older teen he had just married.

Louis was monkish, but not meek, and immediately asserted his authority as king over areas that were certain to cause him trouble. But we'll start discussing those tomorrow.

14 October 2024

Abelard and Heloise, After the Fall

08 January 2023

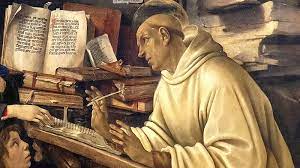

Bernard of Clairvaux

One of seven children (six sons, one daughter), he was sent at the age of nine to a school miles away, where he took a special interest in rhetoric and literature. He also developed a special interest in the Virgin Mary, seeing her as the ideal human intercessor between mankind and God. Later in life he would write several works about her, although he did not accept the idea of the Immaculate Conception.

His mother's death when he was 19 years old motivated him to devote himself to a cloistered life. He joined Cîteaux Abbey, a relatively new establishment (founded 1098) for those who wished to strictly live according to the Rule of St. Benedict. When a scion of one of the noblest families of Burgundy chose the monastic life, his example prompted scores of young men to do the same. By 1115, the community had grown large enough that a new abbey was needed, and Bernard was elected to take a group of 12 monks to the Vallée d'Absinthe and found a new one. He named this the Claire Vallée ("Clear Valley"), and the name Clairvaux became attached to him.

Bernard's example was such that all male members of his immediate family ultimately joined Clairvaux, leaving only his younger sister, Humbeline in the outside world. (She eventually got permission from her husband to enter a Benedictine nunnery.) His brother Gerard, a soldier, joined after being wounded; Bernard made him the cellarer, a job at which he was so efficient that he was sought after for advice by craftsmen of all kinds. Gerard of Clairvaux also became a saint.

A rivalry arose between Clairvaux and Cluny Abbey. Cluny's reputation for monasticism and the physical size of its church made it a little proud, and the growing reputation of Cîteaux and Clairvaux rankled. While Bernard was on a trip away from Clairvaux, the Abbot of Cluny visited and persuaded one of its members, Bernard's cousin Robert of Châtillon, to join Cluny. This bothered Bernard deeply. Cluny criticized the way of life at Cîteaux, causing Bernard to write a defense of it, his Apology. The Apology was so convincing that the abbot of Cluny, Peter the Venerable, affirmed his admiration and friendship. Another person convinced by the Apology was Abbot Suger.

At the Council of Troyes in 1128, Bernard was asked by Pope Honorius II to attend and made him secretary, giving him the responsibility to draw up synodal statutes. He also composed a rule for the Knights Templar. Bernard's reputation had grown to the point that he was sought after as a mediator. In the schism of 1130, when there were two popes, King Louis VI brought the French bishops together to find a way forward. The person chosen to make the final decision on which pope was authentic and which an antipope? Bernard of Clairvaux. I'll tell you more about that, and his further successes, tomorrow.

28 August 2022

Stained Glass

There are some very early (4th- and 5th-century) Christian churches that have, not stained glass, but carefully carved thin slices of alabaster—a precursor to the elaborate stained glass windows of the Middle Ages.

Our earliest references to stained glass for religious purposes in medieval Europe comes from Benedict Biscop, who hired glass workers from France to create windows for his monastery at Monkwearmouth. Here and at his other monastery at Jarrow have been found hundreds of pieces of colored glass and lead (used to hold the glass together). These were constructed in the 7th century. The 10th century saw church windows in Germany, France, and England depicting scenes from the Bible.

I talked about Abbot Suger long ago, who re-built the Abbey of St.-Denis with special attention to the stained glass windows. He wrote down his thoughts and reasoning (and justification for spending an enormous sum of money on the renovations):

All you who seek to honor these doors,

Marvel not at the gold and expense but at the craftsmanship of the work.

The noble work is bright, but, being nobly bright, the work

Should brighten the minds, allowing them to travel through the lights.

To the true light, where Christ is the true door.

The golden door defines how it is imminent in these things.

The dull mind rises to the truth through material things,

And is resurrected from its former submersion when the light is seen.

Suger considered the beautiful windows to have an ennobling effect on the viewer, which was no doubt advantageous for making an impression on the congregation.

Glass-making takes a lot of heat, expertise, and knowledge of rudimentary chemistry to color the glass. What was that about? That is our next topic.

21 October 2012

A Grave Strikes Gold

| Ring inscribed to Aregund (ARNEGUNDIS) |

|

| Belt clasp from Aregund's jewelry collection |

The deceased wore a violet-coloured silk skirt, held in place by a large leather belt that had a sumptuously decorated buckle plate and buckle counter-plate. Her reddish-brown silk tunic, decorated with gold braid, was fastened with a pair of round brooches with a garnet cloisonné decoration. [source]To be frank,* there are some who believe the remains belong to another noblewoman who lived decades later. Most of the reasoning is based on the age of the sarcophagus. The arguments neglect the simple possibility that Aregund was re-interred—not an uncommon occurrence. Even if the identity were up for debate, however, the value of the contents as a glimpse into 7th century Frankish culture is incalculable.

*Yes, that's a pun.

19 September 2012

Abbot Suger

|

| Abbot Suger in stained glass |

The church had existed for centuries, and was rebuilt a few times before Abbot Suger (flourished 1122-1151) arranged the renovation that was to transform ecclesiastical architecture. The major elements of Gothic architecture—elaborate style, ribbed vaulting that supported higher ceilings, pointed arches that enabled larger windows, etc.—already existed, but Suger's efforts brought them together in one building for the first time and created something very different from the massive, dense, dark Romanesque style of building.

Was Suger an architect? A builder? How is it that we so confidently give him credit for this change in ecclesiastical building? Because he did something else that was unique for the era: he told us what he was doing. He left us two works, preserved by the Abbey: Liber de De rebus in administratione sua gestis (The book of deeds done in his administration), and Libellus Alter De consecratione ecclesiae sancti dionysii (The other little book on the consecration of the church of St.-Denis). Translated in 1946 by art historian Erwin Panofsky (previously mentioned here), they tell a tale of a devoted man dedicated to praising God and His creation through every aspect possible of the church that was built to honor Him.

|

| Ambulatory showing ribbed vaulting |

Noble is the work, but the work which shines here so nobly should lighten the hearts so that, through true lights they can reach the one true light, where Christ is the true door… the dull spirit rises up through the material to the truth, and although he was cast down before, he arises new when he has seen this light.Suger made clear that introducing more light to the interior of the church, promoting the use of color, and building in taller elements would help lift the congregants' spirit as well as their eyes upward. He had an enormous amount of money and effort put into the construction of a gold crucifix, 6 meters in height, and gold altar panels; into these panels he says he put:

about forty-two marks of gold; a multifarious wealth of precious gems, hyacinths, rubies, sapphires, emeralds and topazes, and also an array of different large pearlsThe cross is long gone, but the church remains, celebrated as the first truly Gothic church, standing on the Ile de France. A piece of it—Suger's chalice—has made it to North America, however, and stands in the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC. Also, there is a photo-filled blog devoted to Suger right here.

*Pronounced su-zháy.