When the Fatimid caliphate collapsed in 1171 and was replaced by the Ayyubids, ben Moses was replaced by Maimonides. Two years later, ben Moses returned to the position and held it until 1195, when Maimonides regained the position. An account written in 1197, the Megillat Zutta ("Scroll of Zutta"), describes his tenure unfavorably. The author, Samuel ben Hananiah, derogatorily nicknames him "Zutta" meaning "little one," and describes him as a "despotic ignoramus" who gained his power by corruption and informing on fellow Jews.

Besides giving himself the grandiose title of Sar Shalom ("Prince of Peace"), one of his sins was to try to get the local Egyptian governors to act as tax farmers. The Jewish community of Alexandria banned anyone who recognized his authority. Maimonides actually overruled this ban, fearing it would pit Jews against each other. Instead, found a passage in the Pirkei Avot ("Chapters of the Fathers"; a collection of teachings from rabbinic tradition) that forbade the collection of taxes by religious leaders. He used this to excommunicate Sar Shalom ben Moses.

Sar Shalom and Maimonides both died in 1204, after which Maimonides' son, Abraham Maimonides, became Nagid of the Egyptian Jewish community.

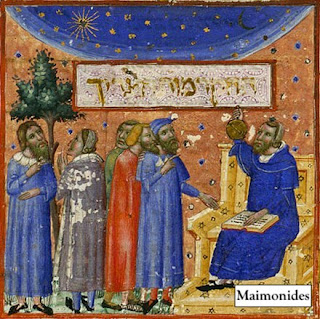

As often as Maimonides has come up in this blog, in over 800 posts I've never given him top billing. I think next time we'll look more closely at