Bacon looked for support and patronage from the papal legate to England, telling him that educational reform was needed. This was one Gui Foucois, although in England he was known as Cardinal Guy de Foulques. The cardinal was not interested in providing financial aid, but was interested in his work and ideas. Unfortunately, without money, Bacon could not afford the writing materials and scientific equipment to produce what he wanted to send.

Then, in 1265, the situation changed. Guy de Foulques was elected Pope Clement IV. Another request to the new pope returned the same result: Clement wanted the information, but would not send money. Bacon could only assemble a shorter work than he wanted to. The result was the Opus Majus or Opus Maius (Latin: "Greater Work"). Its seven sections (which included some of his earlier writings along with new materials) are:

•The Four General Causes of Human Ignorance (believing in an unreliable source, sticking to custom, ignorance shared by others, pretending to knowledge)

•The Affinity of Philosophy with Theology (concludes that Holy Scripture is the foundation of all sciences)

•On the Usefulness of Grammar (a study of Latin, Greek, Hebrew, Arabic)

•The Usefulness of Mathematics in Physics (in this section he proposes changes to fix the Julian calendar)

•On the Science of Perspective (the anatomy of the eye and brain; light, vision, reflection and refraction, etc.)

•On Experimental Knowledge (a review of alchemy, gunpowder, and hypothesizes microscopes, telescopes, eyeglasses, machines that fly, and ships driven be steam)

•A Philosophy of Morality (philosophy and ethics)

It was sent to Clement in late 1267 or early 1268; however, Clement died in 1268. We do not know if he even had opportunity to read what he had requested.

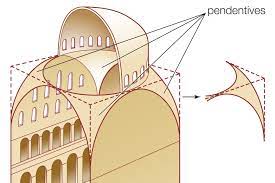

"The Science of Perspective" was about optics. In that section, he discussed the anatomy of the eye, and how light is affected by distance, reflection and refraction. He also goes into mirrors and lenses. Most of this knowledge of optics came from Alhazen's Book of Optics, previously discussed here, and Robert Grosseteste's work on optics based on Al-Kindi, of whom I have never written before; I think there's my next topic.

For more on Bacon, use the search feature in the blog.