On 30 September, 1859, Abraham Lincoln used this expression while addressing the Wisconsin State Agricultural Society when he said:

It is said [redacted] once charged his wise men to invent him a sentence, to be ever in view, and which should be true and appropriate in all times and situations. They presented him the words: "And this, too, shall pass away." How much it expresses! How chastening in the hour of pride! How consoling in the depths of affliction!

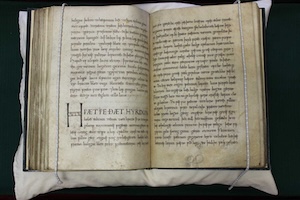

Seems straightforward, and yet it's now time to reveal the [redacted] portion. The words I left out are "an Eastern monarch." Huh? Why not the Western European source of the Exeter Book? One of the earliest translations into Modern English of passages from the Exeter Book was in 1842, the Codex Exoniensis by Benjamin Thorpe. Deor was included, but it seems clear that Lincoln (although widely read) did not get his theme from this work on Old English poetry.

It is likely that he got it from a more popular author, Edward FitzGerald. Known more as the author of The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam, FitzGerald had published a retelling of an old Persian fable, Solomon's Seal, in which a sultan requests of Solomon a motto for a signet that would be useful in both adversity and prosperity, and Solomon offers "This also shall pass away." The story also appears in Jewish folklore, where sometimes Solomon is the king who requests a motto.

Lincoln may have got it from Blackwood's Magazine (1817 - 1980), a British periodical that was also distributed in the United States and featured American authors. An early English appearance of this tale appeared in Blackwood's in 1848.

Ultimately, the saying's origin has been traced to Persian Sufi poets such as Rumi, Sanai, and Attar of Nishapur. In fact, Attar (c.1145 – c.1221) may be the earliest source, and we'll check him out tomorrow.