Cuthbert (c.635 - 687) was a very important saint in Northumbria, but his reputation was enhanced and expanded when Alfred the Great had a vision of Cuthbert that inspired him in his battles against the Danes. Alfred's house of Wessex became particularly devoted to the northern saint, making Cuthbert a saint for all of England. Preserving his remains was a necessity.

Initially buried at Lindisfarne, Danish invasions caused the monks to flee the island in 875, taking Cuthbert's bones along. Bede wrote that Cuthbert was put in a stone sarcophagus, but fortunately for the people in charge of moving him that was abandoned for a wooden coffin. After seven years of relocating to different sites, including Melrose, he was taken to Chester-le-Street, a market town in County Durham, where the body was interred and remained for 112 years at the parish church of St. Mary and St. Cuthbert.

In 995, the coffin was moved to Ripon, again because of the Danes. Upon its return to Chester-le-Street, the wagon carrying the coffin became stuck on the road at Durham. This was seen as a sign that the saint wished his remains to be in Durham, and he was taken to Durham Cathedral.

When William the Conqueror began the Harrying of the North to put down northern rebels, Bishop Ælfwine in 1069 tried to take Cuthbert's body back to Lindisfarne, but he was caught (and imprisoned, where he died).

In 1104, the coffin was opened and his relics taken to a new shrine built for him in Durham Cathedral. At this time a book was found, a Gospel of John called the Cuthbert Gospel; it is the oldest surviving book with its original binding.

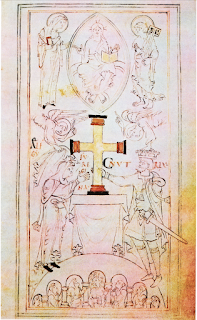

During the Dissolution of the Monasteries by Henry VIII, Cuthbert's shrine was destroyed, but the relics survived interred at the site. A dig at the site in 1827 uncovered the relics and the remains of a wooden coffin (illustrated above), reconstructed from what pieces were salvageable.

All things considered, I am sure Cuthbert would have preferred to remain at Lindisfarne. What made the "Holy Island" so special is worth a closer look...next time.