Piers Gaveston, close friend and favorite of

King Edward II, was exiled from England three times: once by Edward's father and twice by Edward's nobles, but he never stayed away long. He was twice recalled by his friend, but the third time it seems he returned surreptitiously on his own.

His third and final exile leaves us with questions: he was not allowed to be in any of England's possessions, so he could not go to Ireland (the location of his second exile), and could not be in Aquitaine or his home of Gascony. Whatever the case, after only two months of absence, he showed up in England about Christmas 1311, and seems to have joined the king on 11 January, traveling with him to his estates at Tintagel and Wallingford. A week later, in defiance of the Ordinances of 1311, Edward boldly restored all of Gaveston's lands and titles (such as Earl of Cornwall) and declared the reasons for the exile unlawful.

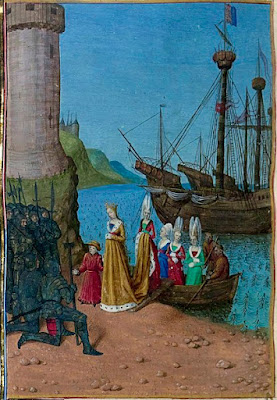

What happens next isn't called a civil war, which usually describes a country divided. In fact, there was very little division: it was simply Edward and Gaveston against almost everyone else. Archbishop Winchelsey of Canterbury excommunicated Gaveston. The nobles, led by Lancaster, assembled for war and some were charged with arresting Gaveston. On 4 May, Edward and Gaveston were together at Newcastle and had to flee Lancaster's forces so rapidly that Edward left behind his treasury and household goods and his pregnant wife! The two split up, Edward heading to York (possible to try to muster some military forces) and Gaveston went to his castle of Scarborough and fortified it. A large force led by four nobles besieged Scarborough, and Gaveston surrendered to them on 19 May under conditions.

The earls of Pembroke, Warenne, and Percy swore to keep him safe while they took him to York to negotiate with the king over his (maybe for real this time) "final" fate. Pembroke went further, pledging to give up his lands and titles if he did not honor the promise of safe conduct. They met with the king and then, since they needed to negotiate with the rest of the ruling class, it was decided that Pembroke would keep custody of Gaveston and take him south. In June, however, while stopping in Deddington, Pembroke decided to spend a night with his wife, who was 12 miles away. He left Gaveston and some guards at a rectory.

Warwick, whom Gaveston had insulted by calling him a "black dog," learned that Gaveston was in Deddington. He surrounded the rectory and took custody of Gaveston—caught him sleeping, in fact, and arrested him before he was fully dressed—and took him to his castle at Warwick. Pembroke, who had chivalrously promised safe conduct for Gaveston with a huge penalty to himself if he failed of his oath, felt that he had been dishonored by Warwick and appealed to have Gaveston returned to his care. No one was willing to support his side; not even Gloucester, whose sister was Gaveston's wife.

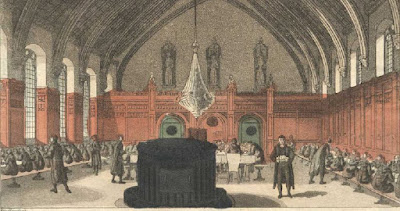

The Earls of Warwick, Lancaster, Hereford, and Arundel gathered at Warwick and condemned Gaveston to death for violating the terms of his last exile. As technically the Earl of Cornwall and brother-in-law of the Earl of Gloucester, it was decided that he deserved a "nobleman's death" by being beheaded. On 19 June he was dragged to Blacklow Hill on Lancaster's land, and while the earls watched from a distance (except the "black dog" Warwick, who was apparently simply content to know that the execution was taking place), two Welsh soldiers handled the matter: one stabbed him with a sword and the second struck his head off. (The illustration above represents Guy de Beauchamp, Earl of Warwick, standing over the beheaded corpse of Gaveston.)

The head was taken to Lancaster. The body was left there where it lay. As an excommunicate, Christian burial was denied him. The corpse was eventually taken in by some Dominicans (Edward was a patron of theirs), and the king paid them for maintaining it while proper interment could be arranged. Edward finally procured a papal absolution in 1315, allowing him to bury his friend with an elaborate ceremony at the Dominican priory. The tomb has since been lost.

Many scholars cannot mention Gaveston as Edward's "friend" without adding the phrase "and lover." What was the precise nature of their relationship? No one knows for sure, but we can look at what little evidence we have of their relationship and make our own guesses. Join me here next time for some creative conjecture.