|

| Detail, Allegory of Good Government Ambrogio Lorenzetti, 1338 |

Sailors found the sand-filled hourglass a definite improvement over its predecessor, the clepsydra* (the water clock), which was affected too much by the swaying of the ocean. When Magellan (c.1480 - 1521) circumnavigated the globe, his fleet had 18 hourglasses per ship, with a page dedicated to turning each one to keep accurate time.

They were also preferable in the early Middle Ages to clocks, because they did not rely on complicated and delicate machinery that needed frequent maintenance.

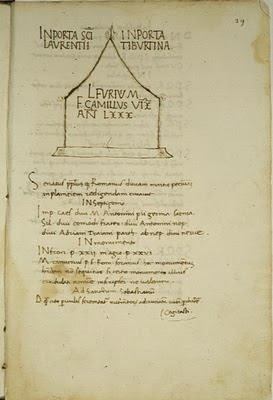

Where and when was the hourglass invented? A story that it was invented in the 800s by a monk at Chartres named Liutprand has no evidence to support it. The clue to the origin may be in the construction. The earliest hourglasses used marble dust for the sand. Also, the hourglass required expertise in glass-blowing. The likeliest location for these two features of the hourglass to be brought together is Italy, particularly Venice, where glass-blowing was a highly developed art and marble was readily available.

By the end of the 14th century, hourglasses were so common that the Goodman of Paris, writing a guidebook for his young wife in the 1390s, included a recipe for preparing the sand/dust for an hourglass:

Take the grease which comes from the sawdust of marble when those great tombs of black marble be sawn, then boil it well in wine like a piece of meat and skim it, and then set it out to dry in the sun; and boil, skim and dry nine times; and thus it will be good.Not only must the hourglass have become common, but its construction was clearly something that could be contributed to by a regular household.

*clepsydra is from the Greek and means "water thief"; they could be very elaborate, but were naturally susceptible to humidity and temperature.