Part of this was not so much a rebirth as an influx of culture from the east: the Byzantine Empire maintained some of what Western Europe "lost" during those centuries. When Otto I married his son, Otto II, to Theophanu, the daughter of the Byzantine Emperor John I Tzimiskes, he opened the door to Byzantine art and increased commerce. Another important figure involved was Gerbert of Aurillac, who became Pope Sylvester II during the reign of Otto III.

Sylvester II introduced the abacus for computation, and wooden terrestrial spheres for the study of the movement of planets and constellations. He composed De rationalis et ratione uti (Of the rational and the use of reason) and dedicated it to Otto III. Promoting reason over faith was an important step in the study of the sciences. Sylvester also promoted the expansion of abbey libraries, particularly at Bobbio Abbey (where St. Columbanus wound up earlier), which had almost 600 works.

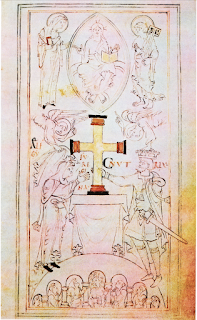

Arts and architecture also stand out in an examination of the Ottonian Renaissance. The revival of the Holy Roman Empire brought inspiration to think on a grander scale and create art and buildings that reflected the grandeur to which the Ottonians believed they were heir. Large bronze doors on churches and gilded crosses became more common. Ottonian patronage of monasteries produced grand illuminated manuscripts. One of the most famous scriptoria was Reichenau, which produced Hermann of Reichenau. This is also the period of the literary output of Hrotsvitha of Gandersheim.

A campaign of renovating churches and cathedrals also took place. (The illustration is an ivory plaque showing Otto I on the left, shown smaller than the saints, presenting Magdeburg Cathedral to Christ.) Longer naves and apses were inspired by Roman/Byzantine basilica. Many of these church designs and re-designs came form the hand of Otto I's brother, Bruno the Great. Bruno extended the cathedral in Cologne to rival the size of St. Peter's in Rome (Cologne Cathedral burned down in 1248, alas). He also built a church dedicated to St. Martin of Tours.

Ivory carving and cloisonné enamels were also widely produced in this era. A major workshop for cloisonné enamels was established by Archbishop Egbert of Trier, using a Byzantine technique of "sunken" enamel, where thin gold wire was soldered to a base, and colored glass melted into the spaces, as opposed to the original style of affixing gemstones as an inlay.

I find Ottonian art, though lovely, does not tickle my interest as much as those "wooden terrestrial spheres" of Pope Sylvester, so I'm going to look into those for next time.