His name was Abū Mūsā Jābir ibn Ḥayyān, and he lived in the 8th century...we think. To be fair, he does not get mentioned until the 10th century by a Baghdad bibliographer who said Hayyan was a disciple of the Shi'ite Imam Ja'far al-Sādiq (who died in 765; Haiyan's writings refer to al-Sādiq as "my master"). That biographer assured his audience that Jabir existed, and made a list of his works, although many later Shi'ite biographers never mentioned Hayyan, and it is considered unlikely that he wrote the many hundreds of texts attributed to him.

Someone had to create the writings attributed to Hayyan, however, and perhaps the name was a pseudonym used to avoid the potential negative publicity because it looked like alchemy, which was rejected by many. Also, the works attributed to him are so many and varied that it is difficult to believe they were the work of one man. He may have inspired a "workshop" of students and followers who produced many of the works. Despite the confusion about his existence, a 271-page biography was written in the 20th century, and is readable at the Library of Congress website (if you can read Arabic, that is).

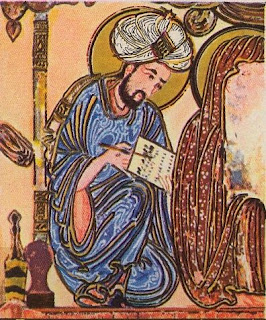

The body of work includes many techniques that are familiar to any high school student who has taken Chemistry: precipitation, crystallization, and distillation. It also teaches procedures for making apparatus (see the illustration) and equipment, for improving the quality of products such as steel, and how to reduce oxidation in metals. We learn from them how to dye and waterproof cotton and leather, the purification of gold, and how to treat cinnabar to extract pure mercury.

You may notice, in large sheets of glass used for, say, store fronts, that there is a greenish hue (most visible if you look at the edge of the glass sheet). Hayyan's writings explain how manganese oxide can be added to glass production to eliminate the greenish hue, resulting in a perfectly clear pane. These writings provide most of what is known about chemical analysis until the 16th century.

I want to go back to the question of Haiyan's identification. One of his writings implies an association with a certain family, the Barmakids. His 10th century biographer, Ibn al-Nadīm (c. 932–995), reports that Hayyan was devoted to Jaʿfar ibn Yaḥyā al-Barmakī, an Abbasid vizier. You may not recognize that name, but I promise you that you have heard of him. In fact, I promise 1001% that you have heard of him. With that teaser/clue, I'll see you tomorrow.