In a few parts of the world today, children are gorging on their haul of candy from trick-or-treating last night. The makers of candy out-do themselves yearly in producing variations on sugar and chocolate and color and texture,

et cetera. But there is hardly anything in children's sacks and plastic jack-o-lanterns today that does not contain sugar.

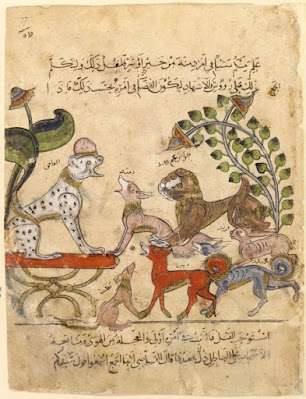

|

| A medieval merchant weighs sugar for sale |

It was soldiers of the Persian Emperor Darius who reported finding, near the Indus River in 510 BCE, reeds which produced honey without bees. Nothing was made of this discovery, but Alexander the Great in 327 BCE learned of it and spread the knowledge to the Mediterranean. By 95 CE, this substance was well-known to the point where the

Periplus Maris Erythræi (Guidebook to the Red Sea) could say there is "Exported commonly ... honey of reeds which is called

sakchar." Not only may this be the first recorded evidence of sugar cane, it is probably also the origin of the later term

saccharine.

But let's skip a bit to the European Middle Ages. According to one scholar, the Muslim conquest of Sicily would have introduced sugar to the West:

"Practically

all the distinguishing features of Sicilian husbandry were introduced by

the Arabs: citrus, cotton, carob, mulberry, both the celso, or black

and the white morrella-sugar cane, hemp, date palm, the list is almost endless." — The Barrier and the Bridge-Historic Sicily, Alfonso Lowe (1972)

When William II of Sicily (1155-1189) built the Benedictine Abbey of Monreale and made it the largest landowner in Sicily after the Crown, it became one of the largest manufacturers of processed sugar in Europe.

Sugar was wonderful, like honey before it. It could be used to sweeten food, make medicine more palatable, and produce new kinds of drinks. It also could add a decorative touch to food: either by adding sparkle to fruit dusted in sugar crystals, or by caramelizing to a lovely brown on cooked foods.

Still, sugar was not as common as everyone would have liked. In 1226,

Henry III (1207-1272) had difficulty finding 3 whole pounds needed for a banquet. Before long, however, production and trade must have increased, because only a generation later, in 1259, Henry could have bought that pound of sugar for only 12 shillings (ginger was 18 shillings, and a pound of cumin was only 2).

To see a collection of recipes from the Middle Ages for sweets, many of which used sugar, see

here.