Walter was ordained on 11 June 1183, so his birth was probably no later than c.1160. He came from Cornwall. Gerald of Wales recorded that Walter's lineage came from Trojans who escaped Troy and settled in Cornwall, but the link to Troy was part of the common myth of Britain's founding. The family was more likely from Normandy, crossing over after 1066. Gerald also refers to Walter being well-educated.

His brother, Roger fitzReinfrid, was a justice under King Henry II, and probably helped Walter gain a position as clerk in the royal chamber. In 1169 he had been given a canonry in Rouen Cathedral, and was made chaplain to Henry the Young King, but after young Henry's rebellion against his father, Walter went back to the elder's court and within a few years was Archdeacon of Oxford.

Walter was sent on diplomatic missions to the continent. The bishop of Lisieux accused Walter of driving him out of his position so that Walter could become a bishop, but there is no evidence that Walter became bishop of Lisieux. Instead, he retuned to England where he was given custody of the abbeys of Wilton and Ramsey, in charge of collecting their revenues for the king.

During this time he was just a valued and trusted courtier, not clergy. He was named Bishop of Lincoln by Henry in May of 1183, but needed to be ordained first, in June, and then in July consecrated as a bishop. He then took part in the election of Baldwin of Forde as Archbishop of Canterbury. As Bishop of Lincoln, he benefitted the schools and was a patron for some of the scholars, but Gerald of Wales claims he was bad for the diocesan finances, running up debt and squandering money.

In November 1184, Rouen needed an archbishop. Rouen had nominated one, but Henry offered them three English candidates, indicating his preference for Walter. Although archbishop was higher status than bishop, Walter was reluctant to accept, because Rouen was financially less stable than Lincoln. The chronicler William of Newburgh recorded that Walter eventually accepted higher status over love of money.

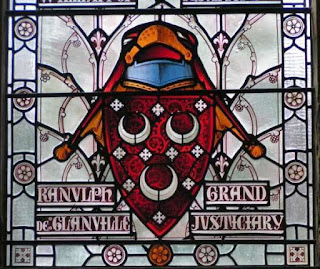

He was still closely tied to Henry's court, and witnessed more of Henry II's royal charters than anyone except Ranulph Glanville. When Henry died and Richard took the throne, he wanted to "clean up his image" because of his earlier rebellion against his father. He sought absolution from Walter and Ranulph. The two archbishops held a ceremony giving Richard absolution, Walter invested him as Duke of Normandy, then followed Richard to England for his coronation.

Richard and Walter remained close. I'll go into their dealings with each other tomorrow.