It might have something to do with the fact that he became the patron of lovers and affianced couples. This is because he was accused of secretly performing Christian marriages at a time when Emperor Claudius Gothicus oppressed Christians in Rome. Since honey was considered an aphrodisiac, it became connected to lovers. We even have the word "honeymoon" to describe the period immediately following marriage when all is sweet. Love connected to honey connected to bees might have been enough.

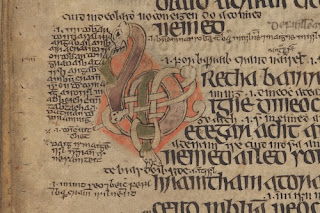

A legend about Valentine—and most likely created later to reinforce his connection to lovers—is that he was a beekeeper himself. In The Golden Legend of Jacob Voragine, there is the following:

When Saint Valentine was brought in an house in prison, then he prayed to God, saying: Lord Jesu Christ very God, which art very light, enlumine this house in such wise that they that dwell therein may know thee to be very God. And the provost said: I marvel me that thou sayest that thy God is very light, and nevertheless, if he may make my daughter to hear and see, which long time hath been blind, I shall do all that thou commandest me, and shall believe in thy God. Saint Valentine anon put him in prayers, and by his prayers the daughter of the provost received again her sight, and anon all they of the house were converted.

This was compiled in the 13th century, a thousand years after Valentine. The Golden Legend was one of the most popular works for a couple centuries, and no doubt inspired many to embellish what they learned about saints' lives. One result was the link between Valentine and bees.

The later legend says that Valentine himself was a beekeeper, gently caring for them and talking to and blessing them with his prayers. The legend extends the story shared above, saying that the provost's daughter loved bees (tricky, when one is blind). This legend says that valentine talked to her about how to care for bees, training her to be a beekeeper, and she eventually regained her sight during this process.

Supposedly, some beekeepers will celebrate 14 February by placing wax candles and honey on the altar.

A casual search about the origin of the word "honeymoon" often turns up the idea that it started in the Middle Ages. That makes its origin fair game for this blog, and we will look into that and report back tomorrow.