He made a non-hostile attempt to gain Northumbria in 1194, when Henry's son Richard Lionheart was king. He offered £9,750 to buy it, which was tempting for Richard. Richard did not care so much for England as he did for two other things: his territory on the continent, and fighting; the money would finance the Third Crusade. William wanted possession of the castles in Northumbria as well, and Richard was not going to give away a potential defensive need.

William focused on uniting Scotland, bringing the formerly independent Galloway under his control, stopping insurrections in Moray and Inverness, and bringing Caithness and Sutherland into line with his rule. William's own banner, which showed a red lion (long after his death he was called "William the Lion") became the Royal Banner of Scotland.

As he aged, however, England in the form of Richard's younger brother, John, thought it a good time to increase control over Scotland. He took an army north, but was bought off with sums of money from William, as well as a promise that William's daughters would marry English nobles. This would give the offspring of those marriages a greater English presence in Scotland. William's son and heir, Alexander, was betrothed to John's daughter Joan. It is believed that Ermengarde managed these negotiations on behalf of her aging husband.

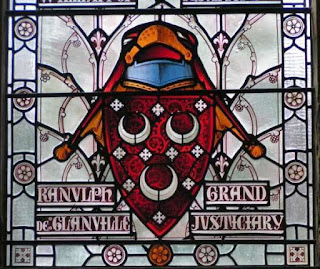

In his lifetime, William managed to not only unite parts of Scotland; he built new settlements, clarified criminal law, and expanded the duties of justices and sheriffs along English lines, a reform movement started by his grandfather, David I. Despite his futile attempts to expand his borders southward, he managed to strengthen Scotland, leaving behind a stronger and more unified country.He died in 1214 at the age of 72 and was buried in Arbroath Abbey, which he founded in 1178. He was succeeded by his son, Alexander II, who learned nothing from his father's travails about trying to get along with England. But let's save that story for next time.