I suppose the problem was that both boys' uncle Möngke, who had been Grand Khan until his death in 1259, did not nominate a successor. Kublai called a kurultai at Kaiping in China—the first time a kurultai to choose a Grand Khan was called outside of Mongol territory. At it, Kublai was elected Grand Khan. Ariq, who had been making alliances with powerful Mongol chiefs, called a kurultai in the Mongol capital Karakoram that elected him Grand Khan.

Their brother Hulagu wanted to support Kublai, but was detained fighting Mamluks and then dealing with hostility from Berke, current ruler of the Golden Horde (begun by all three brothers' uncle, Batu Khan).

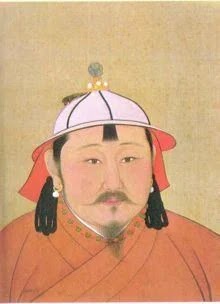

Kublai had Chinese resources behind him. He had been an able administrator, and he promised the Chinese that he could be a benevolent ruler who united Chinese, Mongols, and Koreans. He made grand promises to his potential supporters: lower taxes, rule based on Chinese precedent, and that his era would be one of Zhongtong, "moderate rule."

The Song people in southern China offered no help, but northern China supported him. He had plenty of resources and managed to control three of the four supply lines to Ariq in the capital of Karakoram. Kublai advanced on Karakoram, and Ariq retreated in the only logical direction he had available to him, the way toward the Yenesei River valley in the northwest. Winter set in, forcing Ariq and Kublai to camp and wait for spring.

The Song people of southern China chose this time to rebel, crossing the agreed-upon border of the Yangtze River and recovering some of the territory that Kublai had recently taken. Kublai sent a Chinese diplomat to try to settle the matter, but the diplomat was imprisoned by the Song.

While waiting through the cold season, Kublai continued to gather supplies and recruit soldiers, preparing for civil war. Tomorrow we'll see the results of the fighting.