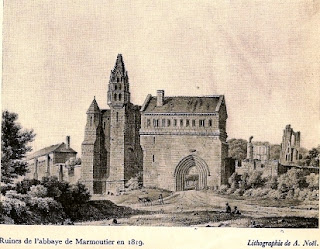

The youngest of five sons, Henry was educated at Cluny, and brought to England by his uncle King Henry I to be Abbot of Glastonbury Abbey. (Henry and Adela were siblings; their father was William the Conqueror.) In 1129 he was made Bishop of Winchester as well, even though that location and the duties of a bishop were a far cry from those of the Abbot of Glastonbury.

Abbot Henry—like King Henry and, indeed, most of the kings of England—disliked being subjected to the ecclesiastical authority of the Archbishops of Canterbury. His idea was to create a third archbishopric in the southwest of England with himself at the head. (The second archbishopric was York.)

His brother the king was not keen on this idea, but Henry gained more prominence than the archbishop when, in March 1139, Henry was named papal legate. This position placed him above Canterbury in the parochial pecking order. If the king was away from England, Henry was the most powerful man in England.

Henry did wonders for the area, commanding hundreds of works projects. He built churches, abbeys, and canals. He also started construction projects at Winchester Cathedral, additions to manors and castles, Winchester Palace in London as the home for bishops of Winchester, and the Hospital of St. Cross at Winchester (which still exists).

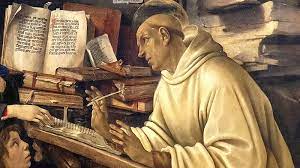

He wrote books and was a patron of authors and bookmakers. William of Malmesbury was a close friend, and Henry sponsored On the Antiquity of the Glastonbury Church by Malmesbury. The largest Bible ever produced, the three-foot-tall Winchester Bible, was sponsored by Henry, as was the Winchester Psalter.

England experienced a period of civil war during this time called the Anarchy. There was a rival who claimed to have a better right to the throne than Stephen. Henry had a choice: support his brother, or the other claimant. We'll explore his choice tomorrow.