King at the time was Philip IV, who in 1307 had managed to get the pope to condemn the Templars, allowing him to seize all their assets for himself. He had three sons and one daughter, Isabella of France. The sons (each of whom had a turn as king) were Louis, who was married to Margaret, daughter of Robert II, Duke of Burgundy; Philip, who married Joan the daughter of Otto IV, Count of Burgundy; and Charles, who married Blanche, another of Otto's daughters.

In 1313, Isabella and Edward II of England visited her parents in France, during which Isabella presented her sisters-in-law with embroidered purses. (Note that these would not have been a modern "lady's purse" but a pouch for carrying coins.) Upon the couple's return to England, a feast was held in their honor. During the gathering, Isabella saw two of the embroidered purses in the possession of two visiting Norman knights, the brothers Walter and Philip Aunay.

Walter was an equerry to Prince Philip, and Philip was an equerry to Prince Charles. An equerry was a "personal assistant" responsible for the horses of a royal personage. Isabella concluded that her sisters-in-law had given the purses to the men for "special favors" and, when she re-visited France in 1314, informed her father of her suspicions. Philip placed the men and his daughters-in-law under surveillance, eventually deterring that Blanche and Margaret had been meeting the two men for drinking and debauchery in the Tour de Nesle, while the third daughter-in-law, Joan, had been aware of the carousing (though not a participant).

Philip gathered enough evidence to accuse those involved publicly. The two sisters were found guilty of adultery, had their heads shaved, and were sentenced to life imprisonment. Joan was found innocent, especially with her husband speaking up for her. (Joan and Philip had a notably romantic marriage: several children in a short space of time, and numerous love letters written by Philip.)

The brothers (under torture) confessed their adultery, were found guilty of lèse-majesté, "crime against the dignity of the crown," and were beaten, skinned alive, covered in boiling lead sulfite, and hanged. Other reports say they were castrated and beheaded. Whatever their fate, it was brutal and terminal.

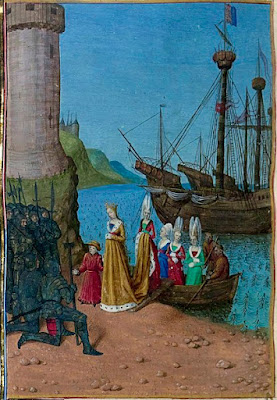

Some think the stress of the Tour de Nesle affair contributed to Philip IV's death later that year. He was succeeded by Louis in 1315. Margaret, held underground at Château Gaillard, became Queen of France automatically. Louis would have liked to avoid this, but he could not get his marriage annulled because to do so required the pope. Why could he not procure an annulment from the pope? Simple: there wasn't one.

I'll explain next time.