James started in 1233 by capturing the town of Burriana, 40 miles north of Valencia along the coast. He spent the next three years expanding from Burriana until, in 1236/7, James' uncle Bernat Guillem de Montpeller captured the town of El Puig, just 15 miles away from Valencia. Legend says that James rode up the highest hill in El Puig and saw Valencia in the distance. Supposedly, his horse reared up and brought its feet down so hard that one of its horseshoes became embedded in the hill and water sprang out of the ground. Another legend says that James had a vision of the Blessed Virgin Mary, and that granted him the ability to take Valencia from the Muslims.

James' forces reached a suburb of Valencia on 22 April 1238, establishing a command post. Because Pope Gregory IX had authorized a Crusade, James was joined by soldiers from Catalonia, England, Germany, Hungary, Italy, and Provence.

Valencia's current ruler, the Tunisian Zayyan ibn Mardanish, called for help from other Muslim allies. Only Tunisia sent help in the form of 12 ships, but they arrived too late. The siege of Valencia made food scarce, and negotiations for handing the city over to James began. On 22 September, the agreement was signed, allowing Muslims in Valencia to either leave and go far south or stay and submit to Christian rule. An estimated 50,000 Muslims left, replaced by about 30,000 Catalan settlers, who were still outnumbered by Muslims.

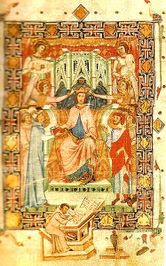

James officially entered the city as its ruler on 9 October (shown in the illustration above by a 19th-century artist), a day that is still celebrated as the Dia de la Comunitat Valenciana, the "Day of the (Autonomous) Community of Valencia."

The mosque was consecrated as a Christian Church. The Virgin Mary became the patron saint of Valencia due to James' vision. For the next several years, James continued to conquer more lands, advancing farther south.

What was it like from the other side of history? What about Valencia and Zayyan ibn Mardanish, seeing a half-millennium occupation of the city being threatened? Let's look at the changing history of Valencia, starting tomorrow.

.jpg)