The first wonder is the lake Lumonoy. In there are sixty islands, and men dwell there, and sixty rocks encircle it, with an eagle's nest on each rock. There are also sixty rivers flowing into that place, and nothing goes out of there to the sea except one river, which is called Lenin.

Loch Lomond, which drains south via the River Leven, has more than 30 islands of various sizes, and they are not surrounded by 60 rocks.

Some of those islands were artificial. People arrived in the area 5000 years ago, during the Neolithic Era, and built up "islands" over the water for safer living. These are called crannogs, and could be a structure on stone pillars or built on wooden stakes (see illustration). A crannog in Lomon called "The Kitchen" was a meeting place for Clan Buchanan from 1225 onwards.

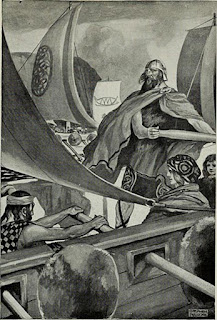

Defense was also the reason why the Romans in the 1st century CE built forts near and around Loch Lomond against the Highland tribes. The need for defense never faded: early Medieval Viking raids dragged their boats overland to put them in the Loch and attack and sack several of its islands.

The loch and its neighboring mountain, Ben Lomond, are part of an area called the Trossachs. The Trossachs were home to Robert the Bruce and William Wallace. The signet ring of Rob Roy Macgregor was a bloodstone from Loch Lomond.

A later legend of the area was that of Reverend Robert Kirk, who researched myths and legends and then wrote a book called The Secret Commonwealth of elves, fauns & fairies. He died before it was published, and sparked his very own legend that the fairies, angry that he revealed their secrets, whisked him away.

The Clan Buchanan, mentioned above, was one of the oldest Highland clans, and we're going to look at their origin tomorrow.