Yrsa was the mother of the 6th century King

Hrolf Kraki. Her name is uncommon, not appearing in any other Norse sources, and there is a common assumption that it relates to Latin

ursus, "bear

." This would align with the Scandinavian tendency to use bear symbolism for extraordinary people, like

Beowulf and

Bothvar Bjarki (who appears in

Hrolf Kraki's Saga, of which Yrsa is a main character).

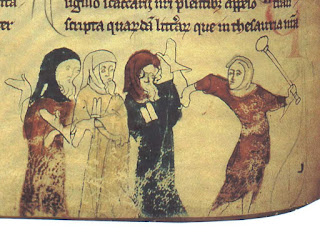

Her story is quite tragic. She is the illegitimate child of Halga (a brother of Hrothgar from the poem Beowulf) and the Saxon Queen Oluf. Halga wooed Oluf, but she wanted nothing to do with him; while he was asleep, she shaved his head and tarred him. Later, he returns and kidnaps her, getting her pregnant in the process. Oluf returns to her home and bears a daughter whom she names Yrsa, who is sent away to be raised with shepherds.

At the age of 12, Halga comes upon the young shepherdess and decides to wed her. (Yes, the age discrepancy is alarming, but Halga had a reputation for pursuing women.) Oluf, learning this, keeps quiet about Ursa's lineage, thinking it a sweet revenge that Halga should wed his own daughter. The pair wed, and have a son, Hrolf, who will some day inherit the kingdom of Denmark.

Hearing that the marriage is a happy one, Queen Oluf decides to ruin them by traveling to Denmark to reveal Yrsa's parentage. Halga accepted this, but Yrsa was ashamed, and left him. She winds up in Sweden where she marries King Aðils (Eadgils in Anglo-Saxon literature). Learning this, Halga goes to Sweden to take her back, but he is killed by Eadgils and robbed. Upset by this, Yrsa curses Eadgils that all his berserker warriors will die. Later, when the warrior Svipdag arrives to "test his skills," she supports him and he slays all the berserkers. Svipdag leaves Sweden for Denmark and enters service under King Hrolf, who has succeeded Halga.

Yrsa saw her son again when he went to Sweden to collect the gold that Eadgils had taken from Halga. Eadgils and Hrolf had recently worked together against their mutual enemy, King Áli, Eadgils' uncle who usurped his throne. Eadgils was reluctant to return the gold, and kept putting off the event. Yrsa gives Hrolf much more gold than he was owed, including Eadgils' favorite gold ring, Sviagris, and gives him and his retainers armor, provisions, and the dozen best horses.

Hrolf and his men leave, Eadgils pursues; Hrolf casts Sviagris on the ground; Eadgils sees it and stoops to pick it up by spearing it with the tip of his spear; while leaning down, Hrolf cuts his back with his sword.

When Hrolf was later killed by his brother-in-law, his sister Skuld ruled Denmark. Yrsa gets revenge for the death of her son by sending a Swedish army that captures Skuld, whom she tortures to death. Hrolf's daughters rule Denmark.

Yrsa's story appears in more than the Hrolf Kraki Saga: Saxo Grammaticus in his Gesta Danorum ("Deeds of the Danish People") says she fled with Hrolf, and suggested the stratagem of casting some of the gold behind to delay the Swedes. Thinking ahead, she had packed gilt-covered copper coins for this purpose.

The Gesta Danorum is another collection of stories like Hrolf Kraki's Saga that offers a lot of information about early Scandinavian beliefs and culture. We'll check that out next.