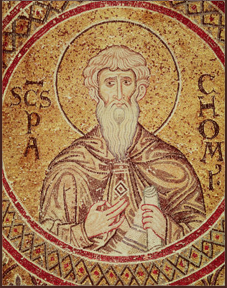

St. Pachomius (c.292 - 348) was born a pagan in Egypt. Drafted into military service by the Roman army at the age of 21, he was put on a ship with several other conscripts heading toward Thebes. There he noticed how Christians kindly brought food daily to the conscripts.

When he left the army a few years later, he investigated Christianity and converted in 314. After seven years as a hermit, he traveled to where St. Anthony was living, modeling his life after Anthony's solitary example. Then, however, a vision told him to create a community where others could join him.

Hermits had clustered together in the same area before, but Pachomius created an organized structure for monks who actually lived and worked together, holding their possessions in common and following a similar schedule. This style of monastic tradition is called cenobitic, a Latin word from the Greek words for "common" [κοινός] and "life" [βίος].

He created the first community shortly after this vision; the first person to join him was his brother John. Many more were to follow. Pachomius built eight monasteries, and the trend caught on: by the time of his death there were hundreds of monks in Egypt following his guidance. He was referred to as "Abba" ("father"), from which the terms "abbot" and "abbey" come. He also wrote the Rule of Pachomius, creating guidelines for communities. It is written in the Coptic (Egyptian) language. He is also given credit for inventing the Prayer Rope to aid in repetitively reciting prayers.

Pachomius never was ordained as a priest. St. Athanasius visited him and wanted to ordain him in 333—Pachomius, like Athanasius, had proven to be a vocal opponent of Arianism—but Pachomius did not want ordination. He died on 9 May 348, we assume from plague.

When he had fallen ill and the end seemed near, he had not named a successor. Many of his followers wanted one monk—a man who was looked up to by many—to assert himself, but Pachomius had different ideas. The succession got a little tricky over the next few years. I'll talk tomorrow about dissent that might have ended the monastery.