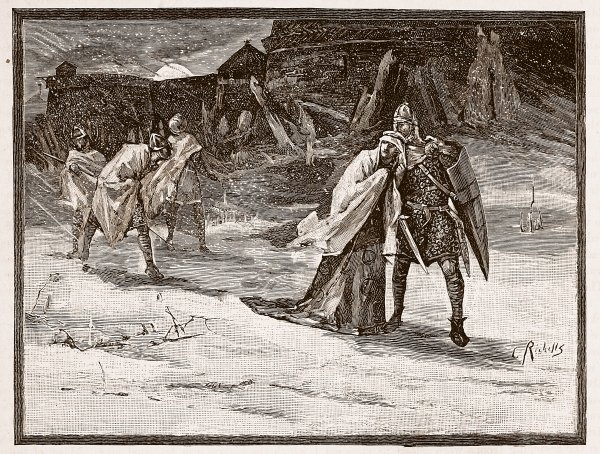

A poor orphan, Dick Whittington (the real Whittington was the son. of a Gloucestershire knight), seeks his fortune in London. Falling asleep on a stoop of a wealthy family, he is given a place to sleep and work as a scullion, cleaning the kitchen. He lives in a rat-infested garret, which is made safe because he has a cat (which he bought for a penny that he earned from shining shoes). Eventually, glad of a room but resentful that he is not paid money for his work, he leaves the house. During his journey, he hears the "London Bells" ringing, and they seem to be telling him to "Turn again, Whittington" and tell him he will become mayor. He returns to the house. At the spot where he heard the bells, the foot of Highgate Hill, is a monument to his cat (see illustration).

Skipping over a bit (a great deal, actually), there is a situation overrun by rats and mice. Dick's cat turns out to be exemplary at dealing with the rodent problem, and he is subsequently offered a great deal of money for the cat. Whittington becomes rich, marries his master's daughter (Alice Fitzwarren, which was the name of the real Whittington's wife), joins his new father-in-law in business, and is later elected mayor of London three times. (He was actually mayor four times, but once was when the king appointed him.)

The folk tale of a man with a useful cat is not unique to England. Two Italian versions are known. A German version is known from the 13th century. A 14th century Persian chronicle tells the same story of a widow's son who made his fortune because of his cat's hunting ability. Although the motif is found much earlier than the English version, the Aarne-Thompson classification system calls it the "Whittington's cat" motif.

Just as today, cats are everywhere, and had both good and bad reputations, which we will study next time.