This blog has mentioned

paganism before, usually in the context of

converting whole nations to Christianity, but what did it look like in Eastern Europe prior to the Christianization that got started around the 8th-9th centuries?

The Byzantine historian Procopius is our source for information about the Vandals and other topics. He tells us about their human sacrifices to their thunder god:

They believe that one of the gods, the creator of lightning, is the lord over all, and bulls are sacrificed to him and other sacred rites are performed. They do not know fate and generally do not recognize that it has any power in relation to people, and when they are about to face death, whether they are seized by illness or in a dangerous situation in the war, they promise, if they are saved, to immediately sacrifice to God for their soul; having escaped death, they sacrifice what they promised, and they think that their salvation has been bought at the price of this sacrifice. They worship rivers, and nymphs, and all sorts of other deities, offer sacrifices to all of them and with the help of these sacrifices they also produce divination. [Book VII of War with the Goths]

Other Western Europe authors refer to the Slavic cult of Radegast, god of the Polabian Slavs, and the sun-god Svarozhich. We might question the accuracy of the interpretation by these "outsiders," but we do have some reports from the "inside." The Russian Primary Chronicle for 980 discusses the Slavic gods prior to conversion:

And Vladimir began to reign alone in Kiev. And he placed idols on the hill outside the palace: a Perun in wood with a silver head and a gold moustache, and Khors Dazhdbog and Stribog and Simargl and Mokosh. And they offered sacrifices and called them gods, and they took their sons and daughters to them and sacrificed them to the devils.

Helmold of Bosau (c.1120 - 1177) wrote his Chronica Slavorum ("History of the Slavs"), covering c.800 - 1171. His report says the Slavs believed in a single heavenly deity who created all the minor spirits that managed elements of nature. These lesser spirits:

...obeying the duties assigned to them, [the deities] have sprung from his [the supreme God's] blood and enjoy distinction in proportion to their nearness to the god of the gods.

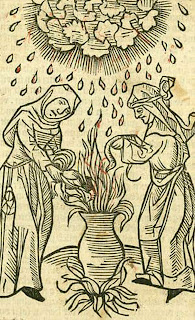

According to Helmold, wheel symbols, and symbols showing multiple arms (see illustration), represented the numerous minor spirits in their relationship to the main deity.

From folklore that has survived, we can gather that there were several supernatural figures that functioned as deities. Outside of the supreme god, Perun was a thunder/sky god (sometimes treated as the supreme god). Veles was his opposite, a god of the underworld. Svarog was the god of the sun/fire and of blacksmiths. Dazhbog (sometimes considered Svarog's son) was the god of domestic fire, the hearth. In other tales, he is the god of rain.

Marzanna was the goddess of winter, and so her presence was dreaded and her departure celebrated, when she withdrew from the world and was replaced by Yarilo, god of spring and agriculture. Vesna was also a goddess of spring, and her name was popularly given to girls.

Mokosh was the goddess of weaving and a protector of women, and Devana the goddess of hunting and the wilderness. Lada was the goddess of love and beauty. She mirrors Persephone, in that she spends part of the year in the Underworld.

There were other minor deities and creatures such as Baba Yaga and Vampir, whose name indicates exactly what you're thinking: he attacks people in the night and sucks blood. Fortunately, being killed by Vampir does not make one a vampire; one becomes a Vampir by being a bad person.

Slavic paganism survived in Russia into the 15th century, and some pagan elements were incorporated into the Russian Orthodox Church. Let's look at the "survival" of paganism in Russia tomorrow.