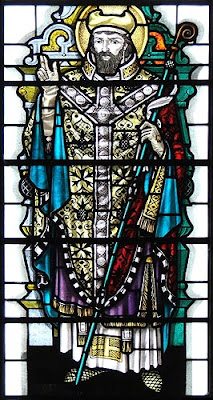

To be confirmed as Archbishop of Canterbury, Dunstan had to go to Rome to receive the pallium from the pope, in this case John XII. His biographer tells us that he was so generous to others during the trip the he ran out of money for himself and his retinue.

Back in England he started making changes. His friend Æthelwold became Bishop of Winchester, and Oswald became Bishop of Worcester. (Oswald, Æthelwold, and Dunstan are referred to as the "Three English Holy Hierarchs" because of their religiou reforms. We'll be getting to Oswald soon.)

Dunstan enforced a spirit of self-sacrifice in the monasteries, and enforced (where he could) celibacy. He forbade selling clergy positions for money, and stopped clergy from appointing relatives to positions under their jurisdiction.

He started a program of building monasteries and cathedrals. The cathedral communities he created were monks instead of secular priests, and in those that existed already with secular priests he insisted they live according to monastic discipline. Priests were encouraged to be educated, and to teach parishioners not only about their religion but also useful knowledge of trades.

For the coronation of King Edgar, Dunstan himself designed the service which became the basis for modern British coronations. Edgar's strong rule and his partnership with Dunstan was considered by contemporary chroniclers as a "Golden Age" for England. The only problem mentioned in chronicles was by William of Malmesbury who wrote that the sailors tasked with patrolling the North Sea shores to guard against Viking invasions were not happy with their post.

Once again, however, Dunstan would clash with the king and lose his standing. Edgar was not the adversary. It was "two kings later" that brought about the end of Dunstan's public career. One more post on Dunstan, and then we will get to the third of the "Holy Hierarchs."

P.S. The illustration is from the anecdote found in the Dunstan link in the first paragraph above, of Dunstan grabbing the devil with red-hot tongs.