He assembled an army to march toward Rome. Stopping in Verona he formed a good relationship with the future Doge of Venice (also named Otto), which helped make relations with Venice better than they had been under Otto's father. Stopping in Pavia at Easter 996, he was formally declared King of Italy and crowned with the Iron Crown of Lombardy.

Before he reached Rome, Crescentius decided he should make peace with the about-to-be-crowned emperor. Pope John XV died before Otto reached Rome. Otto nominated his chaplain, Bruno of Carinthia, who happened to be Otto's cousin (Otto I was the grandfather of both men). He sent Bruno to Rome (Otto was still in Ravenna) with Archbishop Willigis. Crescentius, fearing potential retribution, locked himself away in the Tomb of Hadrian, also known as the Castel Sant'Angelo.

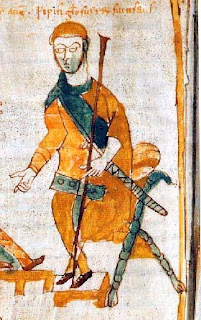

Bruno was confirmed and took the papal regnal name of Gregory V. He crowned Otto as Holy Roman Emperor on 21 May 996 at St. Peter's Basilica (the crown itself shown above). Emperor and pope held a synod a few days later. The Roman nobles that had imprisoned John XV were summoned and banished for their actions, including Crescentius. The new pope, however, did not want to start his reign making enemies; he pleaded for mercy from the emperor. Many were pardoned, and Crescentius was allowed to live in Rome, but he was stripped of the self-given title Patrician of the Romans.

Otto then sent out to restore the glory of the Roman Empire, but he only had six years to do it before his death in January 1002 of a sudden fever while traveling to Rome again to quell unrest against his rule. Malaria was one theory about his illness. Another theory at the time was that the widow of Crescentius had seduced Otto and then poisoned him.

Crescentius? Why would there be hostility from his widow toward Otto? Crescentius was pardoned and lived out his life peacefully in Rome, right? If only that were true. Crescentius continued to cause trouble. I'll go into that tomorrow.