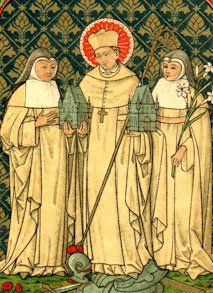

Alèthe and Tescelin had several children: Guy, Gerard, Bernard, André, Barthélémy, Nivard, and Ombeline. Tescelin's rank was not as high as his wife's, but (perhaps through her father's influence), the couple lived very well, able to give their several children good educations while living at the Château de Fontaine-lès-Dijon. The couple were considered by later chroniclers to be notably virtuous. (The illustration shows them both in a stained glass window made for Mariawald Abbey; the whole picture shows them above their son, St. Bernard of Clairvaux.)

Alèthe built a chapel in 1102 near their castle dedicated to St. Ambrose. Her piety strongly influenced her children. When she died at the age of 37, we are told her son Bernard was deeply affected (as I am sure the whole family was). Bernard made the decision to become a monk. Looking for a proper venue, he chose the Abbey at Cîteaux. Legend says that he had a vision of his mother, dressed in white, telling him that God had great plans for him and that he should persuade his brothers to join him.

Bernard and all his brothers went to Cîteaux. All became saints, Bernard of Clairvaux (named for the monastery he himself founded a few years after entering Cîteaux) becoming one of the most celebrated of them. Their sister, Ombeline, entered Holy Orders in 1132 and became abbess at Jully Les Nonains after Bernard demanded the building (a 10th-century castle) to become a convent linked to Molesme.

Alèthe's body was originally interred in the chapel she had built, and she was already considered a saint by the locals. In 1250 the abbot of Clairvaux had the remains brought to Cîteaux to be entombed next to her son, Bernard. At the end of his life, Tescelin joined Cîteaux.

Alèthe had a brother, Andre, who also followed Bernard into Holy Orders, but his life took a slightly different direction from the contemplative: a familiar life, in fact, for readers of this blog. We'll tell the story of André de Montbard tomorrow.