England had refused to allow papal legates on the island for a long time, preferring the relationship between the king and the Archbishop of Canterbury to manage religious decisions. During the reign of King Henry I (reigned 1100 - 1135) he refused eight papal legates prior to Giovanni.

Giovanni stopped at Rouen and sent a letter dated 1 June 1124 to Henry, asking permission to cross the English Channel. He did not receive the permission he sought until 1125. His first mission was to go to Scotland and hold a council to tell the Scottish bishops they were subject to the Archbishop of York. This mission was unsuccessful.

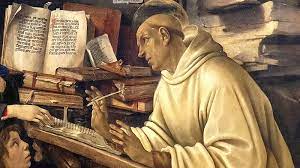

Giovanni held a council at Westminster Abbey (pictured above in its earlier days) on 9 September 1125. It was attended by Archbishop of Canterbury William of Corbeil, Archbishop of York Thurstan of Bayeaux, and about 20 bishops and 40 abbots. Many reforms were declared regarding simony and priestly celibacy, but the issue of primacy between the archbishops was avoided. Instead, Giovanni invited both William and Thurstan to return to Rome with him and meet with the pope.

The three traveled to Rome, but even then Honorius was wary about making a hard and fast decision about the two English offices. One decision Honorius made was that the Bishop of St. Andrews, which was the Roman Catholic diocese of Scotland, would be subject to the Archbishop of York.

Whether York or Canterbury could overrule the other as archbishop was avoided, but Honorius said York would be subject to Canterbury not because Canterbury was somehow more important thanYork but in Canterbury's role as papal legate to England and Scotland. On the other hand, Canterbury could not demand an oath of obedience from York.

Papal legates making demands did not sit well with England (possibly not with anyone), and a rumor spread about Giovanni. Roger of Hoveden's history includes a story from historian Henry of Huntingdon (c.1088 - c.1157) that Giovanni was caught in bed with a woman. Giovanni was suspended from his cardinal position but then restored by Honorius. The rumor of the woman in his bed might explain that.

Why was Giovanni allowed into England after so many papal legates had been refused? Maybe the king wanted the archbishop rivalry resolved and didn't want to anger anyone by doing it himself. Some think it was a quid pro quo situation because of an action taken by the previous pope, Calixtus II. Let's look at that situation tomorrow.