Meanwhile, your forces proceed through the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia, reaching the Saleph River (now called the Göksu in Turkey on a plateau in the Taurus Mountains). The army is sent along a mountain path, while you decide on a shortcut advised by the locals: simply cross the river on your horse.

Holy Roman Emperor Frederick I, called Barbarossa, drowned in the Saleph on 10 June 1190.

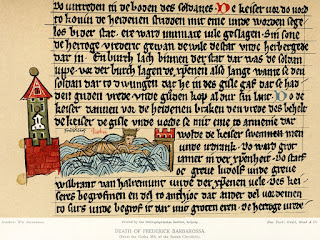

Accounts vary. A biography written within a few years of Frederick's death says he chose to swim the river—possible, but he was 68 years old at the time—and was swept away. A churchman who was with the Crusade says it was a simple swim to refresh himself, but the old man encountered an unexpected current (illustrated in a manuscript of the Saxon Chronicle above). Another says he was thrown from his horse and weighed down by his armor. A contemporary chronicler claims God saved them from an evil man by drowning him in shallow water while the emperor was washing himself.

Whatever the case, the body was subjected to mos Teutonicus, thousands of German soldiers abandoned the Crusade and went home, and Philip of France took the rest to the Holy land where he shared command of the Crusade with Richard I of England, with whom he was not on friendly terms.

Frederick's reputation was such that he is one of those characters who passed into legend, specifically that he is not dead but lies sleeping (like Arthur, with attendants) until such time as his country needs him, either in the Kyffhäuser Mountains in Thuringia or Untersberg. The signal for his revival will be the disappearance of ravens flying around the mountain. His red beard continues to grow, his eyes are only half-shut, and occasionally his hand raises, signaling a boy to go outside and see if the ravens are still flying.

Germany never lost its interest in Barbarossa. The Kyffhäuser Monument (also called Barbarossa Monument) was erected on the anniversary of Frederick's coronation in 1896 to commemorate him and Kaiser Wilhelm I, who was declared the reincarnation of Barbarossa. Hitler named his invasion of the Soviet Union "Operation Barbarossa," although originally called "Operation Otto" after Otto the Great.

These recent posts have, of course, told barely one percent of the extensive accomplishments of Barbarossa. Tomorrow I want to dip into one of his other actions: the revival of the Roman Justinian Code.