|

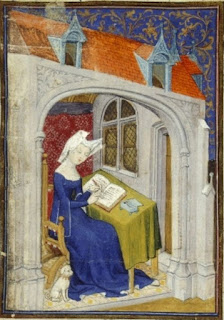

| Christine de Pizan and her dog [link] |

Romsey, which was often the home to noble ladies, gives us an example of pet-based extravagance. John Pecham, who was Archbishop of Canterbury from 1279-1292, criticized the abbess for not providing adequate food to her charges, while at the same time keeping and dogs and monkeys (!) in her chamber.

William Wykeham, Bishop of Winchester, wrote to Romsey's abbess in 1387:

...clear proofs that some of the nuns of your house bring with them to church birds, rabbits, hounds and such like frivolous things, whereunto they give more heed than to the offices of the church, with frequent hindrance to their own psalmody and that of their fellow nuns and to the grievous peril of their souls, therefore we strictly forbid you, ... to bring to church no birds, hounds, rabbits or other frivolous things that promote indiscipline;The keeping of pets was common for the upper classes, and monasteries and abbeys were frequently refuges for noble women who had no prospects of (on interest in) marriage. They clearly did not intend, however, to leave certain luxuries behind, and companion pets were clearly a desirable option.

... whereas through the hunting dogs and other dogs abiding within your monastic precincts, the alms that should be given to the poor are devoured and the church and cloister and other places set apart for divine and secular services are foully defiled, ... we strictly command and enjoin you, ..., that you remove these dogs altogether.