Depictions of the Crucifixion in the 13th century started routinely showing three nails (prior to that, and in the opinion of several Church Fathers, there was one in each foot): one through the overlapping feet and one each in the hand (biologically more appropriate would be in the wrist: the bones of the hand could not support the weight of a body).

Shortly after converting to Christianity and becoming caesar and emperor, Constantine sent his mother, the Empress (later saint) Helena to find the Cross and the Nails used in the Crucifixion. According to the 5th-century author of an ecclesiastical history, Socrates of Constantinople, she was led to the site of what she was seeking by a Jew named Judas Cyriacus.

The nails went in different directions. Socrates said one was made into a bridle used by Constantine, and there are many other locations that claim to have nails. There is a bridle in the cathedral in Carpentras, in Provence that is said to have a nail in it. The Cathedral of Milan also has a bridle that is said to have a nail in it.

The Basilica of Santa Croce in Jerusalem, a church in Rome, has a spike that is supposed to be one.

One was pounded into a thin band and incorporated into the Iron Crown of Lombardy. As it turns out, the band that was supposed to be the nail is made of almost pure silver. Ironically, there is no iron in the "Iron Crown."

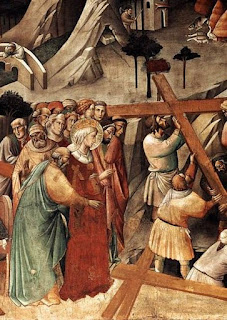

The treasury of Trier Cathedral was sent one (see illustration) from Helena, to (supposedly) commemorate her birthplace.

Bamberg Cathedral (Germany) claims to have part of one nail.

The monastery of San Nicolò l'Arena in Catania (Sicily) has the head of a nail.

The German imperial regalia in the Homburg Palace in Vienna has a nail incorporated into a Lance which is also the Spear of Longinus.

Then, in 2020, a piece of a Holy Nail was found in the Czech Republic. I'll tell you that story tomorrow.