Then the Anarchy happened.

You see, King Stephen had seized the throne after the death of Henry I, even though Stephen had promised support to Henry's daughter Matilda. She was known as Empress Matilda by virtue of marriage to Holy Roman Emperor Henry V. She decided she was owed the throne of England, so she challenged Stephen.

Civil War ensued, and people chose sides. On 2 February 1141, the first clash between the two armies took place at the Battle of Lincoln. Stephen was captured and imprisoned, and Matilda assumed the throne.

Maybe it was because Stephen had not supported Henry in his idea to create a third archbishopric for himself, or simply because Matilda now had control, but Henry chose to support Matilda. But Matilda was not a kind ruler, and Henry changed his mind (especially after Matilda besieged Winchester Castle) bringing the force of the Church in support of the deposed king. Along with Stephen's wife (also named Matilda), forces loyal to Stephen turned the tide and deposed Empress Matilda.

Henry's papal legate position had come from Pope Innocent II, but hen Innocent died on 23 September 1143, the commission ended and Henry lost status. He even went to Rome to try to get it reinstated. He failed, but did manage to get some favors for Glastonbury.

After Stephen's death and the rise of King Henry II, Henry of Blois retired to Cluny and lived with his friend and mentor Peter the Venerable. In January 1164, King Henry II tried to formalize royal authority over the Church in the Constitutions of Clarendon, and Henry was one of the bishops forced to sign it. This later led to the problem with and trial of Thomas Becket, over which Henry presided.

Henry died on 8 August 1171. His exact burial site is disputed.

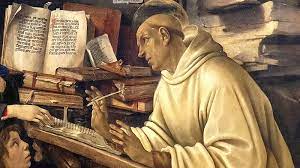

In his time he supported many art and architectural projects (the illustration was made by an artist from Belgium during Henry's time, depicting him as a patron of arts). One of his projects (we believe) was the Winchester Bible, the largest Bible ever made by hand (although incomplete). Let's take a look at that tomorrow.