One of seven children (six sons, one daughter), he was sent at the age of nine to a school miles away, where he took a special interest in rhetoric and literature. He also developed a special interest in the Virgin Mary, seeing her as the ideal human intercessor between mankind and God. Later in life he would write several works about her, although he did not accept the idea of the Immaculate Conception.

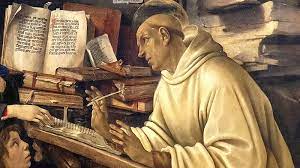

His mother's death when he was 19 years old motivated him to devote himself to a cloistered life. He joined Cîteaux Abbey, a relatively new establishment (founded 1098) for those who wished to strictly live according to the Rule of St. Benedict. When a scion of one of the noblest families of Burgundy chose the monastic life, his example prompted scores of young men to do the same. By 1115, the community had grown large enough that a new abbey was needed, and Bernard was elected to take a group of 12 monks to the Vallée d'Absinthe and found a new one. He named this the Claire Vallée ("Clear Valley"), and the name Clairvaux became attached to him.

Bernard's example was such that all male members of his immediate family ultimately joined Clairvaux, leaving only his younger sister, Humbeline in the outside world. (She eventually got permission from her husband to enter a Benedictine nunnery.) His brother Gerard, a soldier, joined after being wounded; Bernard made him the cellarer, a job at which he was so efficient that he was sought after for advice by craftsmen of all kinds. Gerard of Clairvaux also became a saint.

A rivalry arose between Clairvaux and Cluny Abbey. Cluny's reputation for monasticism and the physical size of its church made it a little proud, and the growing reputation of Cîteaux and Clairvaux rankled. While Bernard was on a trip away from Clairvaux, the Abbot of Cluny visited and persuaded one of its members, Bernard's cousin Robert of Châtillon, to join Cluny. This bothered Bernard deeply. Cluny criticized the way of life at Cîteaux, causing Bernard to write a defense of it, his Apology. The Apology was so convincing that the abbot of Cluny, Peter the Venerable, affirmed his admiration and friendship. Another person convinced by the Apology was Abbot Suger.

At the Council of Troyes in 1128, Bernard was asked by Pope Honorius II to attend and made him secretary, giving him the responsibility to draw up synodal statutes. He also composed a rule for the Knights Templar. Bernard's reputation had grown to the point that he was sought after as a mediator. In the schism of 1130, when there were two popes, King Louis VI brought the French bishops together to find a way forward. The person chosen to make the final decision on which pope was authentic and which an antipope? Bernard of Clairvaux. I'll tell you more about that, and his further successes, tomorrow.