[This is Part 3; the other 3 parts address Gothic Culture & History, Gothic Architecture, and Fiction.]

|

| Augustus W. Pugin |

In 1740, the reputation of the term "Gothic" took an odd turn. The style of architecture

mis-named Gothic had been thoroughly denigrated in the previous century, but an 18th century antiquarian trend toward discovering the past and a re-awakening of interest in traditional church views combined to create a movement that looked to the past for inspiration rather than the future.

The so-called "Gothic Revival" grew over time, and influenced art and architecture throughout Europe, and reached Australia, Southern Africa and the Americas. Its spiritual center was England, however, and it found its true champion in the artist, architect and critic Augustus Welby Pugin (1812-1852).

|

| House of Lords, Westminster |

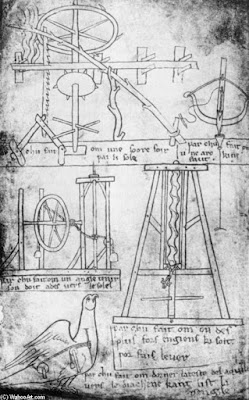

Pugin's father was a draughtsman who came to England from France, married Catherine Welby, and settled down to write volumes on architecture—notably

Specimens of Gothic Architecture and the three-volume

Examples of Gothic Architecture—and to teach his son to draw. Pugin worked in his father's office in his youth, but eventually started getting work of his own. An early job was to design furniture for Windsor Castle. Years later, after dabbling in bringing furniture and carvings from Flanders to England, he was convinced to go into architecture. His business of supplying architectural pieces to people building in the Gothic style failed. He went back to designing for others. He was 18 years old.

At 22, he converted to Roman Catholicism, which lost him some business but introduced him to new contacts. He was employed to make alterations and additions to Alton Towers by the 16th Earl of Shrewsbury, and then to build St. Giles Catholic Church, and then to design the Catholic church of Sts. Peter and Paul in Newport. His reputation grew, and he designed houses and churches and furnishings to satisfy the fans of the Revival. The interior of the House of Lords in Westminster is one of his most visible achievements.

But just because something

can be done doesn't mean it

should be done. The Gothic Revival under Pugin left nothing out: any feature of Gothic architecture could be re-used, no matter its original purpose. The Pugin chair pictured here, for instance, reminds me of one at the Pugin exhibit "A Gothic Passion" that I saw at the Victoria & Albert Museum in London in the early 1990s.* The back is carved as if it were the frame of a stained glass window. It employs the pointed arch that was such an important development in Gothic architecture because of the way it distributed the weight of the stone. Here, something that was vitally functional is made purely decorative. The hanging finials in the front of the chair are another architectural detail that, here, would be functional only if they were intended to impede the swinging of a small child's legs. It seems to me that much of the Gothic Revival style was intended to be as ornamental as possible, employing details that once had purpose but are, in this case, only something to look at, and that possibly make the object less comfortable.

*

This may be the first time I have inserted my opinion and personal observation into a post, so I ask your forgiveness if it detracts from the information. I had a very strong negative reaction when I first saw Pugin's work, particularly a chair that had pointed arches upside-down carved into its back.