The second king was Edmund, and he was becoming increasingly disillusioned with Dunstan as a minister because of the lies of others. Dunstan was prepared to leave, even asking representatives of the kingdom of East Anglia to let him go with them when they left Edmund's court.

Before that event, however, Edmund went out hunting in the Mendip Forest. I'll let someone else take it from here:

He became separated from his attendants and followed a stag at great speed in the direction of the Cheddar cliffs. The stag rushed blindly over the precipice and was followed by the hounds. Eadmund endeavoured vainly to stop his horse; then, seeing death to be imminent, he remembered his harsh treatment of St. Dunstan and promised to make amends if his life was spared. At that moment his horse was stopped on the very edge of the cliff. Giving thanks to God, he returned forthwith to his palace, called for St. Dunstan and bade him follow, then rode straight to Glastonbury. Entering the church, the king first knelt in prayer before the altar, then, taking St. Dunstan by the hand, he gave him the kiss of peace, led him to the abbot's throne and, seating him thereon, promised him all assistance in restoring Divine worship and regular observance. [link]

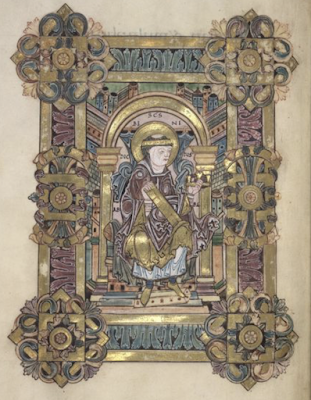

Dunstan's childhood dream of restoring Glastonbury Abbey to its former glory was in his grasp. Edmund also sent Æthelwold to help. The two began to rebuild the abbey (see illustration for how it might have looked before Henry VIII) and established Benedictine Rule, although probably not as strictly as it was being reformed on the continent. Unlike Æthelwold, Dunstan was not opposed to the presence of secular priests.

Dunstan had a brother, Wulfric, who was given responsibility for the material upkeep of the abbey, so that the cloistered monks did not have to "break enclosure." The first project was to rebuild the church of St. Peter.

Things were looking up for Dunstan and Glastonbury. When Edmund was assassinated in 946, his successor's policies looked to make things even better for Dunstan. Eadred promoted unification of all parts of the kingdom, both Saxon and Danish, along with moral reform and rebuilding of churches. Dunstan's position grew in authority. But Eadred died in 955, and Eadwig was a very different kind of king.

The 45-year-old Dunstan clashed with the 15-year-old Eadwig on the very day of the coronation, setting up another turn of the wheel. I'll tell that awkward story next time.