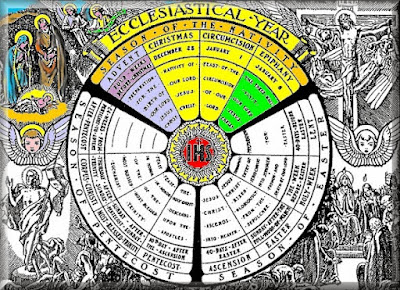

Among other things, Trent determined the liturgical calendar (see illustration). Part of this process involved establishing definitive feast days for saints, which may not be altered or added to except by the pope.

In the process, it was necessary to decide definitively which saints deserved feast days or other types of mention. Pope Pius V (ruled 1566 to 1572) removed some names he considered insignificant, such as St. Elizabeth of Hungary (mentioned here) and St. Anthony of Padua (mentioned here). How to determine of saints were worthy of inclusion in the liturgical year, with their names to be specifically mentioned at Mass, was to rank them. The 13th century created a ranking system of Double, Semidouble, and Simple. Pope Clement VIII created the rank of Major Double in 1602. Over the centuries, popes added or subtracted (mostly added) saints' rankings to the calendar. What do these terms signify about the saint in question?

As it happens, we do not know why the word "double" is used; it may have to do with the antiphon (a chant used as a refrain) were doubled before and after the psalms. Another theory is that in Rome before the 9th century it was customary to have two sets of Matins (prayers at dawn) on major feast days. Whatever the origin, the importance of a saint's feast day could be designated (in ascending order) as Simple, Semidouble, and Double; the Double rank included further strata (in ascending order) of Double, Greater/major Double, Double of the II Class, Double of the I Class.

With "semantic satiation" occurring by now, and the word "double" looking and sounding strange to the reader, we have to ask "Why?" What need was satisfied by ranking saints' days?

Well, a saint's feast day had its own liturgy, unique from the ordinary Sunday Mass. If a saint's day feel on Sunday, which Mass do you celebrate? Easter had a special Mass; what do you do if Easter Sunday happens to fall on 17 April, the Feast Day of the 2nd century Pope Anicetus? Sure, he fought against Gnosticism and was (supposedly) martyred—and already has more than one mention in this blog—but is he worth more than Easter? Well, his rank is Simple, so no, Easter liturgy takes precedence. (Actually, Easter takes precedence over every saint; I just wanted an example of a floating holiday.) This overlapping of important days was called an "occurrence"; the lower-ranking day could be referred to as a "commemoration" during the liturgy of the higher-ranking day.

On an ordinary weekday, the priest celebrating Mass can choose to use a liturgy of his choice: either a normal "votive Mass" or Mass for the dead (if a funeral was needed), or he could choose the liturgy for martyrs Cosmas and Damian on 27 September.

There were so many changes to this system that going into more detail would require listing all the revisions over the years, so we will just jump to the later 20th century. Pope Pius XII in 1955 abolished the Semidouble rank, turning them all to Simples (making the choice of which liturgy to perform easier), and reduced all Simples to Commemorations (so no liturgy, just an "honorable mention" during Mass if desired). Pope Paul VI in 1969 further simplified the liturgical choices, eliminating Commemorations and reforming other ranks to Solemnities (truly important days involving the Trinity, or Jesus, Mary, Joseph, or VIP saints; these days include a Vigil), Feasts (pretty much just the Nativity and the Resurrection), and Memorials, most of which were optional.

Thousands of men and women were designated saints in the first 1400 years of Christianity, and at least one dog. Recent centuries trimmed down that list, recognizing that many were likelynot real people, but simply anecdotes intended to teach a moral lesson.

Except the dog; that one happened. You probably want that one explained.