Besides studying all the known Jewish religious texts, Moses ben Maimon (1138 - 1204) was a rabbi, knew medicine (he was the personal physician of Saladin) and astronomy. He became well-known and liked in Egypt (he lived in Cairo for a time), but he also had some very vocal critics.

The chief issue is that he took a rationalist-philosophical approach to the world and came to conclusions that were contradictory to what many believed. A couple that I have mentioned before were:

•The power of prophecy does not require intervention by God. Any human being, through the application of logic and reason, study and meditation, has the potential to become a prophet.

•In a treatise on resurrection, he emphasizes that God would not violate the laws of Nature which He has created, and therefore any bodily resurrection would only be temporary; true resurrection to come is spiritual.

He really got under people's skin when he criticized the Geonim, the rabbinic scholars who took donations from sponsors. Maimonides felt they should learn a profession and support themselves, as he did.

After his death, his The Guide for the Perplexed was translated into Hebrew (he had been writing in Arabic). Jewish scholars around the Mediterranean who were familiar with Arabic philosophy could see and parse the influences on Maimonides' work, but when his work became accessible to European Jews it kicked off a new stage of controversy.

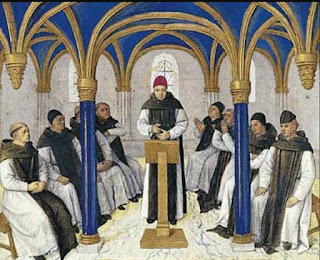

In the early13th century, European scholars were unfamiliar with concepts of science and philosophy. Aristotle's works were just being re-discovered in the West thanks to Arabic translations in Spain from the original Greek versions. Other works of philosophy were starting to spread because 1204 was not only Maimonides' death but also the Sack of Constantinople, which started bringing Greek treasures—including intellectual treasures—to the West.

I'll go into more about how the controversy heated up in Europe tomorrow. Meanwhile, you can read a little more about Maimonides and the intellectual evolution of Western Europe in my post on Scholasticism.