There was Motsognir | the mightiest made

Of all the dwarfs, | and Durin next;

Many a likeness | of men they made,

The dwarfs in the earth, | as Durin said.

11. Nyi and Nithi, | Northri and Suthri,

Austri and Vestri, | Althjof, Dvalin,

Nar and Nain, | Niping, Dain,

Bifur, Bofur, | Bombur, Nori,

An and Onar, | Óin, Mjothvitnir.

12. Vigg and Gandalf | Vindalf, Thorin,

Thror and Thrain | Thekk, Lit and Vit,

Nyr and Nyrath,-- | now have I told--

Regin and Rathsvith-- | the list aright.13. Fili, Kili, | Fundin, Nali15. There were Draupnir | and Dolgthrasir,

Hor, Haugspori, | Hlevang, Gloin,

Dori, Ori, | Duf, Andvari,

Skirfir, Virfir, | Skafith, Ai.

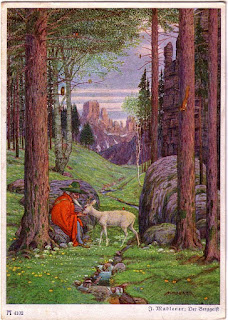

You can see here the source of familiar dwarf names in his stories, and one extra: Gandalf (appropriately tinted gray). The name is interpreted as "wand elf" and seems to denote either a magical dwarf or a dwarf with a staff. Speaking of Gandalf the Grey, the illustration above is a postcard in Tolkien's possession which he said was the inspiration for the character of Gandalf. It is called Der Beggeist ("The Mountain-spirit"), and was painted by a German artist in the 1920s. The character's colors are off for Gandalf, and his obvious connection to nature suggests rather Gandalf's colleague Rhadagast the Brown, but something about it caused Tolkien to label it "Origin of Gandalf."

Now, to get from a 20th-century scholar back to medieval scholarship: Tolkien wrote poems, one of which, Fastitocalon, referenced a giant mythological sea creature. This was from an Old English poem called "The Whale," and it's worth taking a look at next time.