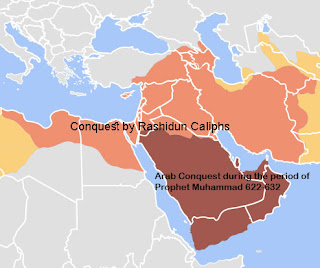

Abu Bakr died two years later and was succeeded by ʿUmar ibn al-Khaṭṭāb, Muhammad's father-in-law. Umar had originally been opposed to Muhammad, but had come around. As the second caliph, he expanded the caliphate to cover two-thirds of the Byzantine Empire as well as part of Persia. Jewish tradition claims Umar allowed Jews into Jerusalem to worship. Umar was assassinated in November 644 by a Persian slave.

Umar's successor was Uthman, who advanced Islam into Byzantine territory until he was assassinated in June 656.

From 656 until 661 the caliphate was headed by ʿAlī ibn Abī Ṭālib, a member of Muhammad's clan and had married Muhammad's daughter, Fatima. His election was opposed by the members of Uthman's clan, and they did not recognize his authority. After Ali, there were those who felt the caliphate should be ruled by heredity, as opposed to being ruled by political choices. Ali's rule was the beginning of the Shia-Sunni civil war.

Sunnis say that the first four caliphs were all related to Muhammad through marriage and were among his closest companions. They were the Rashidun, the "Rightly Guided" caliphs. The Shia group (about 10-15% of Muslims) claims that originally Muhammad chose Ali as his successor, but he was passed over for Abu Bakr. They said Islam should be led by descendants of Muhammad and Ali. Sunnis believe the leader should be chosen by political means, as were Abu Bakr, Umar, and Uthman.

This clash between the two groups ended the Rashidun Caliphate and gave rise to the Umayyad Caliphate, which has been mentioned a few times in this blog. The Umayyads expanded Islam even further and started clashing with Western Europe. We will see how that turned out tomorrow.