Although Pope Gregory IX felt it his duty to protect the Jews, he had issues with their Talmud, the collection of Jewish laws and practices. Was it harmful and heretical, or simply a way of life that was different?

A converted Jew had presented to Gregory 35 places in the Talmud that he considered blasphemous to Christianity. This led to the Disputation of Paris (about which I really should write a post soon). After the Disputation, a tribunal was assembled to decide whether the Talmud was dangerous to Christianity. One of the men involved, Odo of Châteauroux (c.1190 - 25 January 1273), was chancellor of the University of Paris. The decision of Odo and the tribunal was that the Talmud was heretical and should be burned.

In 1242, 24 cartloads of copies of the Talmud and other Hebrew books were burned at a ceremony in Paris. Skip forward to 1243, however, and Pope Innocent IV was on the throne of Peter. At first, he continued the policy of Gregory, and Talmuds were gathered to be destroyed. He began to question, however, whether this policy was not in opposition to the Church's traditional stance of tolerance for Jews.

In 1247, the pope listened to complaints brought to him by some Jews, and he asked Odo to take a second look, but this time to try to see it through the eyes of the Jewish rabbis. Was the Talmud truly heretical and a danger to Christianity, or merely misguided and could be treated simply as an error-prone text and studied as such, the way philosophy would be treated. He thought that the Talmud might prove harmless, and that the confiscated copies might be returned.

Odo was having none of it, and he condemned the Talmud again, in May 1248. Innocent listened carefully, and also listened to the rabbis who claimed that they could not understand the Bible if they did not have their Talmud, which was so intertwined with the Old Testament. Against the objections of Odo and others, Pope Innocent decreed that the Talmud should not be burned, merely censured as erroneous insofar as Christianity is concerned. He decreed that the Talmuds in possession should be returned to their owners.

The popes after Innocent continued this policy.

A converted Jew had presented to Gregory 35 places in the Talmud that he considered blasphemous to Christianity. This led to the Disputation of Paris (about which I really should write a post soon). After the Disputation, a tribunal was assembled to decide whether the Talmud was dangerous to Christianity. One of the men involved, Odo of Châteauroux (c.1190 - 25 January 1273), was chancellor of the University of Paris. The decision of Odo and the tribunal was that the Talmud was heretical and should be burned.

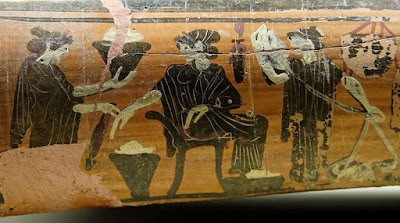

|

| Burning the Talmud |

In 1247, the pope listened to complaints brought to him by some Jews, and he asked Odo to take a second look, but this time to try to see it through the eyes of the Jewish rabbis. Was the Talmud truly heretical and a danger to Christianity, or merely misguided and could be treated simply as an error-prone text and studied as such, the way philosophy would be treated. He thought that the Talmud might prove harmless, and that the confiscated copies might be returned.

Odo was having none of it, and he condemned the Talmud again, in May 1248. Innocent listened carefully, and also listened to the rabbis who claimed that they could not understand the Bible if they did not have their Talmud, which was so intertwined with the Old Testament. Against the objections of Odo and others, Pope Innocent decreed that the Talmud should not be burned, merely censured as erroneous insofar as Christianity is concerned. He decreed that the Talmuds in possession should be returned to their owners.

The popes after Innocent continued this policy.