The border separating England from Scotland almost became a little thicker last week, and this week is the anniversary of its creation, with the Treaty of York on 25 September 1237. The border had, not surprisingly, fluctuated over the years, but the Treaty of York effectively stopped Scotland's attempts to push south.

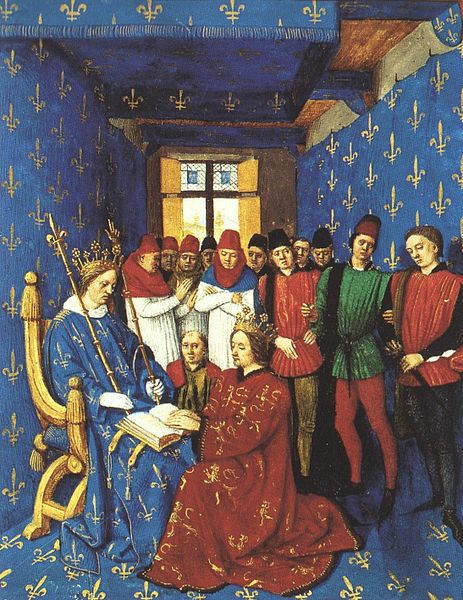

The Treaty itself was not a grandly historical moment—and historians often skip over it when discussing relations between the two countries—but the event is interesting because of the account by Matthew Paris and the relationship between the participants, King Alexander II of Scotland and King Henry III of England. The two of them worked well together when they had to; after all, Alexander had married Henry's sister Joan in 1221, and Alexander's sister had married Henry's former regent, the influential Hubert de Burgh.

But Matthew Paris (known for being less than objective or factual) made the Treaty far more interesting by lying about the signing. He had nothing good to say about Alexander, portraying him as uncivil and aggressive toward the attending papal legate, Otho, who had been invited by Henry. Supposedly, Alexander claimed that, since no papal legate had ever been to Scotland, he would not allow any papal legate to visit the country. This was untrue, since papal legates had visited Scotland under Alexander's grandfather, uncle, and father; Alexander himself had seen a papal legate earlier.

The Treaty did not end a vicious war or curtail a rebellion; in some ways, it merely ratified current conditions. Scotland gave up claims to Northumberland, Cumberland, and Westmorland, and gave up a debt of 15,000 silver marks owed to Scotland that had been given to King John. Scotland also forgave the breaking of promises to marry some of Alexander's sisters to prominent Englishmen. England, in turn, gave Scotland specific territories within Northumberland and Cumberland, with complete judicial control over actions within.

Both countries also ratified that previous treaties and agreements that did not contradict the Treaty of York would be honored.

All in all, the Treaty did not seem to do much, and yet unfulfilled aristocratic marriage promises, royal debts, and border disputes had been enough to cause war, or at least great hostility between nations. The document signed at York that day may well have prevented much strife that otherwise would have followed.

The Treaty itself was not a grandly historical moment—and historians often skip over it when discussing relations between the two countries—but the event is interesting because of the account by Matthew Paris and the relationship between the participants, King Alexander II of Scotland and King Henry III of England. The two of them worked well together when they had to; after all, Alexander had married Henry's sister Joan in 1221, and Alexander's sister had married Henry's former regent, the influential Hubert de Burgh.

But Matthew Paris (known for being less than objective or factual) made the Treaty far more interesting by lying about the signing. He had nothing good to say about Alexander, portraying him as uncivil and aggressive toward the attending papal legate, Otho, who had been invited by Henry. Supposedly, Alexander claimed that, since no papal legate had ever been to Scotland, he would not allow any papal legate to visit the country. This was untrue, since papal legates had visited Scotland under Alexander's grandfather, uncle, and father; Alexander himself had seen a papal legate earlier.

The Treaty did not end a vicious war or curtail a rebellion; in some ways, it merely ratified current conditions. Scotland gave up claims to Northumberland, Cumberland, and Westmorland, and gave up a debt of 15,000 silver marks owed to Scotland that had been given to King John. Scotland also forgave the breaking of promises to marry some of Alexander's sisters to prominent Englishmen. England, in turn, gave Scotland specific territories within Northumberland and Cumberland, with complete judicial control over actions within.

Both countries also ratified that previous treaties and agreements that did not contradict the Treaty of York would be honored.

All in all, the Treaty did not seem to do much, and yet unfulfilled aristocratic marriage promises, royal debts, and border disputes had been enough to cause war, or at least great hostility between nations. The document signed at York that day may well have prevented much strife that otherwise would have followed.