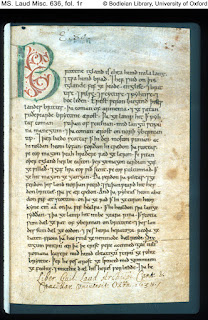

It is, of course, historically highly inaccurate. The scribes were working with the best knowledge they had at the time, and motives ascribed to important political figures are suspect. Here is the opening, (collated from different manuscripts):

The island Britain is 800 miles long, and 200 miles broad. And there are in the island five nations; English, Welsh (or British), Scottish, Pictish, and Latin. The first inhabitants were the Britons, who came from Armenia, and first peopled Britain southward. Then happened it, that the Picts came south from Scythia, with long ships, not many; and, landing first in the northern part of Ireland, they told the Scots that they must dwell there. But they would not give them leave; for the Scots told them that they could not all dwell there together; "But," said the Scots, "we can nevertheless give you advice. We know another island here to the east. There you may dwell, if you will; and whosoever withstands you, we will assist you, that you may gain it." Then went the Picts and entered this land northward. Southward the Britons possessed it, as we before said. And the Picts obtained wives of the Scots, on condition that they chose their kings always on the female side; which they have continued to do, so long since. And it happened, in the run of years, that some party of Scots went from Ireland into Britain, and acquired some portion of this land. Their leader was called Reoda, from whom they are named Dalreodi.For all its flaws, its nearly 100,000 words are, in many cases, the only human viewpoint we have on certain centuries. Also, its status in literature is assured as "the first continuous history written by Europeans in their own language."