The Talmud [late Hebrew talmūd, "instruction"] is the body of Jewish civil and ceremonial law. It includes the Mishnah (exegetical material embodying the oral tradition of Jewish law) and the Gemara (rabbinical commentaries on the Mishnah). The Talmud had a rocky existence in Christian Europe, even at the hands of one of the popes who was most supportive of the Jews, Gregory IX.

Pope Gregory IX (c.1145 - 1241) was responsible for the Decretals (a codification of canon law that some say was designed to establish his authority over the Church) and the Papal Inquisition (and let us not forget his part in the demonization of cats). This centralization of power of the papacy seemed to inspire him to be the guardian of all God's children, however. He was steadfast in his protection of persecuted Jews, so long as they were not guilty of what he considered to be sins.

In 1233, for instance, Jews in France complained to Gregory that they were being mistreated. He declare that any imprisoned Jews were to be set free and not injured in their person or their property, so long as they agreed to forsake usury (the practice of charging high rates of interest, considered to be sinful due to the Bible).

In the 1234 Decretals, Gregory declared the doctrine of perpetua servitus iudaeorum. That is, the Jews were in perpetual political servitude until Judgment Day, making them officially second-class citizens in the Empire. As abhorrent as this was, it also made Gregory treat them as a group that needed his protection, so that in 1235 he re-affirmed an earlier papal bull, Sicut Judeis ["and thus, to the Jews"], which declared their right to enjoy lawful liberty.

1236 was a busy year for Gregory. He presented a list of charges against Emperor Frederick II concerning offenses against the Jews. In September he wrote to several bishops of France, requiring them to make sure that Crusaders who had killed and robbed Jews make full restitution. He also wrote to King Louis IX of France concerning the same.

Gregory had a serious problem, however, with the Talmud. He had to determine if it fell into the category of "heresy." His conclusion was harsh, but fortunately not universally accepted. We will look at that tomorrow.

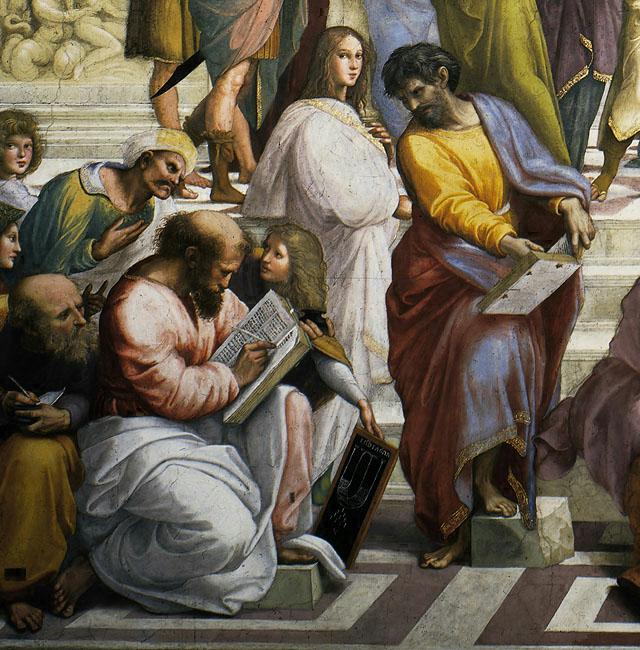

|

| Talmud from 13th-14th centuries |

In 1233, for instance, Jews in France complained to Gregory that they were being mistreated. He declare that any imprisoned Jews were to be set free and not injured in their person or their property, so long as they agreed to forsake usury (the practice of charging high rates of interest, considered to be sinful due to the Bible).

In the 1234 Decretals, Gregory declared the doctrine of perpetua servitus iudaeorum. That is, the Jews were in perpetual political servitude until Judgment Day, making them officially second-class citizens in the Empire. As abhorrent as this was, it also made Gregory treat them as a group that needed his protection, so that in 1235 he re-affirmed an earlier papal bull, Sicut Judeis ["and thus, to the Jews"], which declared their right to enjoy lawful liberty.

1236 was a busy year for Gregory. He presented a list of charges against Emperor Frederick II concerning offenses against the Jews. In September he wrote to several bishops of France, requiring them to make sure that Crusaders who had killed and robbed Jews make full restitution. He also wrote to King Louis IX of France concerning the same.

Gregory had a serious problem, however, with the Talmud. He had to determine if it fell into the category of "heresy." His conclusion was harsh, but fortunately not universally accepted. We will look at that tomorrow.