Yesterday's post on St. Menas and the flasks of water leads to a discussion of oleum martyris, literally "oil of martyrs" but more generically called "Oil of Saints," a liquid said to have flowed (in some cases, still flowing) from the bodies or relics or burial places of saints. It may also refer to water from wells associated with them or near their burial sites, as well as to oil in lamps or in other ways connected to the saint. Liquid was an easy souvenir to take away from a site, and liquid is an easy thing to apply to a sick person, if you believe the liquid has some connection to a cure, such as association with a saint.

Many saints have this phenomenon associated with them. The earliest was St. Paulinus of Nola, who died in 431.* Oil was poured over his relics, and then collected in containers and cloths and given to those in need of cures. The historian Paulinus of Pétrigeux (writing about 470) tells us that by his day this practice was being used on relics of saints who were not martyred as well. The relics of St. Martin of Tours (316-397) were used in this way. St. Augustine of Hippo (354-430) records that a dead man was resurrected in this way by use of oil of St. Stephen, the first Christian martyr who was stoned in 34.

One of the most famous oils is still "in production," as it were. In Eichstadt in Bavaria, at the Church of St. Walburga (c.710-779), a liquid flows from the stone and metal on which are placed the relics of this saint. The church is owned by the Sisters of Saint Benedict, who collect the liquid and give it away in small vessels. This fluid has been analyzed and discovered to be nothing more than water (suggesting that it is created by condensation from humid air on a cool slab), but its contact with the saint's relics make it valuable to the faithful.

Another source of "oil" is the relics of St. Nicholas of Myra. His relics in the Church of San Nicola in Bari produce a fluid called "Manna of St. Nicholas" and believed to have curative properties.

Most accounts of "Oil of Saints" are connected with saints from the first several centuries of the Common Era, with only one each from the 11th, 13th and 14th centuries.

*St. Menas lived and died earlier, but the curative properties of his burial place were not discovered until later in the 5th century.

23 January 2013

22 January 2013

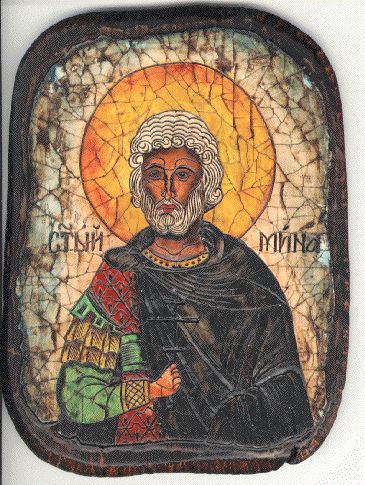

St. Menas

In 1905, C.M. Kaufman of Frankfort led an expedition into Egypt and made excavations that unearthed the legacy of St. Menas. He found the ruins of a monastery, a well, a basilica, many inscriptions asking the saint's aid, and thousands of miniature water pitchers and oil lamps.

Based on the inscription on the vessels found by Kaufman (Eulogia tou agiou Mena = Remembrance of St. Menas), the vessels were intended as souvenirs of the saint. The location excavated was one of the most popular pilgrimage sites in the 5th and 6th centuries, and flasks like those found by Kaufman had been found for years in Africa, Spain, Italy, France and Russia. It was assumed that they contained oil, but now it is thought that they probably held water from the local well, and likely were supposed to have curative powers.

According to the Catholic Encyclopedia, Menas was martyred under Emperor Diocletian in 295 (other sources say 309—there was more than one Menas in the first few centuries of the Common Era, and it is difficult to reconcile all the records). An Egyptian by birth, Menas had actually served in the Roman army, but left the army when he learned of the poor treatment of Christians by the empire. He went into retreat, engaging in fasting and prayer. He came out of retreat to proclaim the Christian faith in the middle of a Roman religious festival. He was dragged before the authorities, scourged and beheaded. Here is where the legend truly begins: supposedly, his body was to be burned, but the flames worked on it for three days without destroying it.

The martyr's body was brought to Egypt and placed in a church, and his name began to be invoked by Christians in need. Then an angel appeared to Pope Athanasius, telling him to have the body transported into the western desert outside Alexandria. While being transported, the camel carrying it stopped at one point and would not move. The followers buried the body in that spot.

Later, the location was forgotten, but a shepherd noticed that a sick sheep fell on a certain spot and rose up cured. The story spread that this spot cured illnesses. When the leprous daughter of the Emperor Zeno (c.425-491) traveled there for a cure, she received a vision at night from St. Menas, telling her that it was his burial place. Her father had the body exhumed, a cathedral built, and a proper tomb prepared for St. Menas. A city and industry sprang up, since so many people came to be cured. Water from the well dug in that location began to be bottled for pilgrims and supplicants. These flasks were found in several countries, but it wasn't until Kaufman's 1905 expedition that their true origin was uncovered.

Based on the inscription on the vessels found by Kaufman (Eulogia tou agiou Mena = Remembrance of St. Menas), the vessels were intended as souvenirs of the saint. The location excavated was one of the most popular pilgrimage sites in the 5th and 6th centuries, and flasks like those found by Kaufman had been found for years in Africa, Spain, Italy, France and Russia. It was assumed that they contained oil, but now it is thought that they probably held water from the local well, and likely were supposed to have curative powers.

According to the Catholic Encyclopedia, Menas was martyred under Emperor Diocletian in 295 (other sources say 309—there was more than one Menas in the first few centuries of the Common Era, and it is difficult to reconcile all the records). An Egyptian by birth, Menas had actually served in the Roman army, but left the army when he learned of the poor treatment of Christians by the empire. He went into retreat, engaging in fasting and prayer. He came out of retreat to proclaim the Christian faith in the middle of a Roman religious festival. He was dragged before the authorities, scourged and beheaded. Here is where the legend truly begins: supposedly, his body was to be burned, but the flames worked on it for three days without destroying it.

|

| "Menas flask" in the Louvre |

Later, the location was forgotten, but a shepherd noticed that a sick sheep fell on a certain spot and rose up cured. The story spread that this spot cured illnesses. When the leprous daughter of the Emperor Zeno (c.425-491) traveled there for a cure, she received a vision at night from St. Menas, telling her that it was his burial place. Her father had the body exhumed, a cathedral built, and a proper tomb prepared for St. Menas. A city and industry sprang up, since so many people came to be cured. Water from the well dug in that location began to be bottled for pilgrims and supplicants. These flasks were found in several countries, but it wasn't until Kaufman's 1905 expedition that their true origin was uncovered.

21 January 2013

Electrical Engineers

Electrical and Mechanical Engineers have their own patron saint—at least, in the British Army they do.

Saint Eligius (or Eloi, or Eloy) was born about 588 near Limoges, France. His father recognized skill in him, and sent him as a young man to a noted goldsmith to learn a trade. He became so good at it that he was commissioned by Clothar II, King of the Franks, to make a golden throne decorated with precious stones. With the materials he was given, he made the throne with material left over ("enough for two" it was said). Since it was not unknown for artisans to use less than they were given and hide away the excess for their own wealth, Eligius' honesty in designing the throne was noteworthy.

On the death of Clothar, his son Dagobert became King of the Franks. Dagobert (c.603 - 19 January 639) appointed Eligius his chief councilor. Dagobert is considered the last king of the Merovingian line to wield any real power on his own. After him came the weak kings that allowed the Mayors of the Palace to establish the Carolingian dynasty.

Dagobert and Eligius became very close, and it is said that Dagobert relied in Eligius heavily—sometimes exclusively—for advice. With Dagobert's help (i.e., money) Eligius established several monasteries, purchased and freed slaves brought into Marseilles, sent servants to cut down the bodies of hanged criminals and give them decent burial.

In 642, the goldsmith and councilor became a cleric when Eligius was made Bishop of Noyon. He undertook to convert the non-Christians in his diocese, and preached against simony in the church. Some of his writings have survived.

But it was the legends after his death that gave him his current reputation. Of course he is the patron of goldsmiths and craftsmen, and is often depicted holding a bishop's crozier in one hand and a hammer in the other. By extension, he is the patron of all metalworkers, which would include blacksmiths. Over time, the skills of the blacksmith evolved into the skills of mechanical engineers. But that is not to say that Eligius was not a problem-solver on a par with engineers. The legend tells that he was once faced with a horse that refused to cooperate with being shod. Eligius cut off the leg that needed shoeing, put a horseshoe on the detached hoof, then re-attached the leg to the horse! The Corps of Royal Electrical and Mechanical Engineers of the British Army have taken Eligius for their patron saint.

Saint Eligius (or Eloi, or Eloy) was born about 588 near Limoges, France. His father recognized skill in him, and sent him as a young man to a noted goldsmith to learn a trade. He became so good at it that he was commissioned by Clothar II, King of the Franks, to make a golden throne decorated with precious stones. With the materials he was given, he made the throne with material left over ("enough for two" it was said). Since it was not unknown for artisans to use less than they were given and hide away the excess for their own wealth, Eligius' honesty in designing the throne was noteworthy.

On the death of Clothar, his son Dagobert became King of the Franks. Dagobert (c.603 - 19 January 639) appointed Eligius his chief councilor. Dagobert is considered the last king of the Merovingian line to wield any real power on his own. After him came the weak kings that allowed the Mayors of the Palace to establish the Carolingian dynasty.

Dagobert and Eligius became very close, and it is said that Dagobert relied in Eligius heavily—sometimes exclusively—for advice. With Dagobert's help (i.e., money) Eligius established several monasteries, purchased and freed slaves brought into Marseilles, sent servants to cut down the bodies of hanged criminals and give them decent burial.

In 642, the goldsmith and councilor became a cleric when Eligius was made Bishop of Noyon. He undertook to convert the non-Christians in his diocese, and preached against simony in the church. Some of his writings have survived.

But it was the legends after his death that gave him his current reputation. Of course he is the patron of goldsmiths and craftsmen, and is often depicted holding a bishop's crozier in one hand and a hammer in the other. By extension, he is the patron of all metalworkers, which would include blacksmiths. Over time, the skills of the blacksmith evolved into the skills of mechanical engineers. But that is not to say that Eligius was not a problem-solver on a par with engineers. The legend tells that he was once faced with a horse that refused to cooperate with being shod. Eligius cut off the leg that needed shoeing, put a horseshoe on the detached hoof, then re-attached the leg to the horse! The Corps of Royal Electrical and Mechanical Engineers of the British Army have taken Eligius for their patron saint.

20 January 2013

Prester John, Part 2

|

| Prester John on his throne |

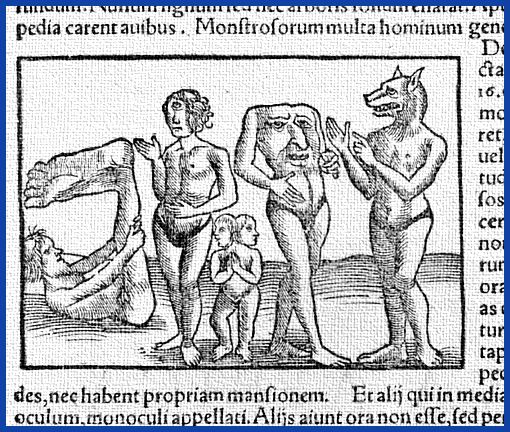

So what was the world of Prester John like?

He ruled over 72 countries, for one thing. In those lands could be found men who lived for 200 years, men with horns on their foreheads or three eyes, unicorns, and women warriors who fought on horseback. Several of the features of his world were apparently "borrowed" from the 3rd century Romance of Alexander, such as cannibals, elephants, headless men whose faces were on their torsos, pygmies, rivers that flowed out of Eden, and the fountain of youth.

|

| Inhabitants of Prester John's land |

19 January 2013

Prester John, Part 1

That "inaccessible area" in Asia mentioned in the Finding Paradise entry fascinated Europeans. Knowledge of the lands to the east was rare, and accounts of travels in that direction were devoured. Marco Polo's tales were only one example.

The 3rd century apocryphal text Acts of Thomas tells of St. Thomas and his attempts to convert India to Christianity. Although not included in the definitive collection of books of the Bible, it was still copied and read (Gregory of Tours made a copy), and sparked the imagination: what if there were a thriving community of Christians in exotic India, cut off from Europe and desirous of contact?

In the 12th century, a German chronicler and bishop called Otto of Friesling recorded that in 1144 he had met a bishop from Syria at the court of Pope Eugene III. Bishop Hugh's request for aid in fighting Saracens resulted in the Second Crusade. During the conversation, however, Bishop Hugh mentioned a Nestorian Christian (Nestorians and their origin were briefly mentioned here) who was a priest and a king, named Prester John, tried to help free Jerusalem from infidels, bringing help from further east. He had an emerald scepter, and was a descendant of one of the Three Magi who brought gifts at Jesus' birth.

The idea of Prester John, a fabulously wealthy and well-connected Christian potentate poised to help bridge the gap between West and East, captured the imagination. A letter purporting to be from Prester John appeared in 1165. The internal details of the letter suggest that the author knew the Acts of Thomas as well as the 3rd century Romance of Alexander.

The letter became enormously popular; almost a hundred copies still exist. It was copied and embellished and translated over and over. Modern analysis of the evolution of the letter and its vocabulary suggest an origin in Northern Italy, possibly by a Jewish author.

At the time, however, no analysis was needed for people to act. Pope Alexander III decided to write a letter to Prester John and sent it on 27 September 1177 via his physician, Philip. Philip was not heard from again, but that did not deter the belief in Prester John at all.

The 3rd century apocryphal text Acts of Thomas tells of St. Thomas and his attempts to convert India to Christianity. Although not included in the definitive collection of books of the Bible, it was still copied and read (Gregory of Tours made a copy), and sparked the imagination: what if there were a thriving community of Christians in exotic India, cut off from Europe and desirous of contact?

In the 12th century, a German chronicler and bishop called Otto of Friesling recorded that in 1144 he had met a bishop from Syria at the court of Pope Eugene III. Bishop Hugh's request for aid in fighting Saracens resulted in the Second Crusade. During the conversation, however, Bishop Hugh mentioned a Nestorian Christian (Nestorians and their origin were briefly mentioned here) who was a priest and a king, named Prester John, tried to help free Jerusalem from infidels, bringing help from further east. He had an emerald scepter, and was a descendant of one of the Three Magi who brought gifts at Jesus' birth.

The idea of Prester John, a fabulously wealthy and well-connected Christian potentate poised to help bridge the gap between West and East, captured the imagination. A letter purporting to be from Prester John appeared in 1165. The internal details of the letter suggest that the author knew the Acts of Thomas as well as the 3rd century Romance of Alexander.

The letter became enormously popular; almost a hundred copies still exist. It was copied and embellished and translated over and over. Modern analysis of the evolution of the letter and its vocabulary suggest an origin in Northern Italy, possibly by a Jewish author.

At the time, however, no analysis was needed for people to act. Pope Alexander III decided to write a letter to Prester John and sent it on 27 September 1177 via his physician, Philip. Philip was not heard from again, but that did not deter the belief in Prester John at all.

18 January 2013

Parochial School

One of the decrees that came out of the Fourth Lateran Council of Pope Innocent III was that "every cathedral or other church of sufficient means" was to have a master or masters who could teach Latin and theology. These masters were to be paid from the church funds, and if the particular church could not support them, then money should come from elsewhere in the diocese to support the masters. The interest of the Roman Catholic Church in providing education has a long history.

This did not start in 1215, actually: the Third Lateran Council of 1179 (called by Pope Alexander III) had already declared that it was the duty of the Church to provide free education "in order that the poor, who cannot be assisted by their parents' means, may not be deprived of the opportunity of reading and proficiency."

One wonders how carefully churches complied with this. Because the school was integral to the church it was attached to, records are not as abundant as they might be if the school were a separate legal entity with its own building, property taxes, et cetera. We have to look for more anecdotal and incidental evidence.

Among Roger Bacon's unedited works is a reference about schools existing "in every city, castle and burg." John of Salisbury (c.1120-1180), English author and bishop, mentions going with other boys as a child to be taught by the parish priest. (Note that this is long before the Lateran Council decrees; it seems they may have simply affirmed and extended a long-held practice.)

Schools for young boys stayed attached to churches for a long time. A late-medieval anecdote of Southwell Minster in Nottinghamshire (pictured here; believed to be the alma mater of Thomas Cranmer, Archbishop of Canterbury under Henry VIII) tells that a visiting clerk (priest) complained that the noise of the boys being schooled was so great that it disturbed the services taking place. And Shakespeare's Twelfth Night acknowledges these schools with the line "Like a pedant that/Keeps a school i' the Church." It would be a long time before schools for the young were deemed to need their own buildings.

This did not start in 1215, actually: the Third Lateran Council of 1179 (called by Pope Alexander III) had already declared that it was the duty of the Church to provide free education "in order that the poor, who cannot be assisted by their parents' means, may not be deprived of the opportunity of reading and proficiency."

One wonders how carefully churches complied with this. Because the school was integral to the church it was attached to, records are not as abundant as they might be if the school were a separate legal entity with its own building, property taxes, et cetera. We have to look for more anecdotal and incidental evidence.

Among Roger Bacon's unedited works is a reference about schools existing "in every city, castle and burg." John of Salisbury (c.1120-1180), English author and bishop, mentions going with other boys as a child to be taught by the parish priest. (Note that this is long before the Lateran Council decrees; it seems they may have simply affirmed and extended a long-held practice.)

Schools for young boys stayed attached to churches for a long time. A late-medieval anecdote of Southwell Minster in Nottinghamshire (pictured here; believed to be the alma mater of Thomas Cranmer, Archbishop of Canterbury under Henry VIII) tells that a visiting clerk (priest) complained that the noise of the boys being schooled was so great that it disturbed the services taking place. And Shakespeare's Twelfth Night acknowledges these schools with the line "Like a pedant that/Keeps a school i' the Church." It would be a long time before schools for the young were deemed to need their own buildings.

17 January 2013

Finding Paradise

|

| Higden's map, with Eden (and East) at the top |

It certainly wasn't in Europe, which was fairly well traveled, and so the medieval mind had to look beyond the lands they knew. The 13th century Hereford map (a mappa mundi of the T-O pattern; see the link above) places Eden on an island near India, surrounded by not only water but also a massive wall. Ralph Higden places it not only in the less-understood-to-Europeans Asia, but makes clear it is an inaccessible part of Asia (you have to explain why no one has stumbled upon it and returned with the news).

Hrabanus Maurus was a little more cautious:

Many folk want to make out that the site of Paradise is in the east of the earth, though cut off by the longest intervening space of ocean or earth from all regions which man now inhabits. Consequently, the waters of the Deluge, which covered the highest points of the surface of our orb, were unable to reach it. However, whether it be there, or whether it be anywhere else, God knows; but that there was such a spot once, and that it was on earth, that is certain. [De universo (Concerning the world)]A German priest of the 15th century, Meffreth, seems to be the only person who thinks himself qualified to actually answer the question "Wouldn't Eden have been washed away in Noah's Flood?" He has left us a sermon in which he claims that Eden exists on an extremely tall mountain in Eastern Asia—so tall, that the waters that covered Mt. Ararat merely lapped at the base of Eden on this mountain. He further explains that four rivers pour from Eden at such a height that the roar they make when descending to the lake at the foot of the mountain has rendered the locals completely deaf.

After the 15th century, we find few references to a terrestrial location of Paradise. As man started to circumnavigate the globe and explore the interiors of more continents, it became clear that finding Eden was not going to be a simple matter of traveling.

16 January 2013

Grammar

"Grammar" comes from the Greek gramma, meaning "letter of the alphabet" or "thing written." Their word grammatike meant "the art of letters." The Romans pulled this word into Latin unaltered, and it eventually slid into Old French where it became gramaire, and thence to Modern English and the word whose study American schoolchildren try to avoid today.

Grammar had its fans in the Classical and early Medieval eras, however, and none more zealous than Priscianus Caesariensis. We don't know too many details about Priscian, but we know he flourished around 500 CE, because that's about when his famous work on grammar appears.

According to Cassiodorus (c.485-c.585), who was writing during the administration of Theodoric of the Ostrogoths, Priscian was born in Caesarea, in what is now Algeria. Cassiodorus himself lived for a while in Constantinople, and he tells us that Priscian taught Latin in Constantinople for a time.

Priscian wrote a work called De nomine, pronomine et verbo (On noun, pronoun and verb), probably as an instructional tool for his Greek-speaking students. He also translated some Greek rhetorical exercises into Latin in Praeexercitamina (rhetorical exercises). There were also some minor works that don't concern us, because we need to talk about his 18-volume masterpiece, Institutiones grammaticae (Foundations of grammar). He patterned it works of Greek grammar by Apollonius Dyscolus and the Latin grammar of Flavius Caper. His numerous examples from Latin literature mean we have fragments of literature that would otherwise have been lost to us.

Priscian became popular: his work was quoted for the next few centuries, and copies became numerous enough—and his scholarship good enough—that this work became the standard grammar text for 1000 years after his time. We know a copy made it to England by 700; it was quoted by Bede and Aldhelm and copied by Hrabanus Maurus. It was a standard text centuries later at Oxford and Cambridge.

Manuscripts (there are about 1000 copies extant) exist from as early as the 9th century, and in 1470 it was still important enough that it was printed in Venice.

Grammar had its fans in the Classical and early Medieval eras, however, and none more zealous than Priscianus Caesariensis. We don't know too many details about Priscian, but we know he flourished around 500 CE, because that's about when his famous work on grammar appears.

According to Cassiodorus (c.485-c.585), who was writing during the administration of Theodoric of the Ostrogoths, Priscian was born in Caesarea, in what is now Algeria. Cassiodorus himself lived for a while in Constantinople, and he tells us that Priscian taught Latin in Constantinople for a time.

Priscian wrote a work called De nomine, pronomine et verbo (On noun, pronoun and verb), probably as an instructional tool for his Greek-speaking students. He also translated some Greek rhetorical exercises into Latin in Praeexercitamina (rhetorical exercises). There were also some minor works that don't concern us, because we need to talk about his 18-volume masterpiece, Institutiones grammaticae (Foundations of grammar). He patterned it works of Greek grammar by Apollonius Dyscolus and the Latin grammar of Flavius Caper. His numerous examples from Latin literature mean we have fragments of literature that would otherwise have been lost to us.

Priscian became popular: his work was quoted for the next few centuries, and copies became numerous enough—and his scholarship good enough—that this work became the standard grammar text for 1000 years after his time. We know a copy made it to England by 700; it was quoted by Bede and Aldhelm and copied by Hrabanus Maurus. It was a standard text centuries later at Oxford and Cambridge.

Manuscripts (there are about 1000 copies extant) exist from as early as the 9th century, and in 1470 it was still important enough that it was printed in Venice.

15 January 2013

"Grammar" "School"—Part 2 of 2

Yesterday we looked at the use of the word "school" in the Middle Ages. Today, let's look at the descriptive term "grammar" when applied to schools.

There is a document from the late 11th century that refers to a scola grammatice [grammatic/grammar school]. We see that and similar phrases becoming more common in the 1200s. In 1387 we get the first reference in English to a "gramer scole" by John of Trevisa (briefly mentioned here), who is translating Ralph Higden's Polychronicon* and uses the phrase to refer to a school in Alexandria.

But what did they mean by "grammar" school? Was it all just about teaching grammar. Well, in a word, probably "yes." The term grew to distinguish those schools from the more involved curriculum of the schools that were tackling the seven Liberal Arts—Grammar, Rhetoric and Logic made up the foundational "Trivium" while the higher learning of the Quadrivium meant studying Arithmetic, Geometry, Music, Astronomy. (The first three were all about mastering language, the four were all about mastering mathematics.)

What was covered in "grammar" schools? Well, it was synonymous with what a later age called the study of "letters," and comprised learning from great writings. Grammar school was all about reading great literature from the past and committing the lessons found therein to heart. One learned how the great writers—who could on rare occasions be pagan writers, but were mostly the Church Fathers, as well as the Latin Bible—constructed their brilliant sentences and built their arguments.

Of course, these great minds of the past did not write in English, and so the study of "grammar" could not truly be undertaken until one learned Latin. For young boys beginning instruction—usually at a nearby church under the tutelage of a priest—the first stage was learning Latin.

Latin grammar had been dissected and discussed at great length by scholars in the past, particularly by two Latin writers named Priscian and Donat. But let's save them for tomorrow.

*This work was an attempt to write a universal history, hence the name meaning "many times."

There is a document from the late 11th century that refers to a scola grammatice [grammatic/grammar school]. We see that and similar phrases becoming more common in the 1200s. In 1387 we get the first reference in English to a "gramer scole" by John of Trevisa (briefly mentioned here), who is translating Ralph Higden's Polychronicon* and uses the phrase to refer to a school in Alexandria.

But what did they mean by "grammar" school? Was it all just about teaching grammar. Well, in a word, probably "yes." The term grew to distinguish those schools from the more involved curriculum of the schools that were tackling the seven Liberal Arts—Grammar, Rhetoric and Logic made up the foundational "Trivium" while the higher learning of the Quadrivium meant studying Arithmetic, Geometry, Music, Astronomy. (The first three were all about mastering language, the four were all about mastering mathematics.)

What was covered in "grammar" schools? Well, it was synonymous with what a later age called the study of "letters," and comprised learning from great writings. Grammar school was all about reading great literature from the past and committing the lessons found therein to heart. One learned how the great writers—who could on rare occasions be pagan writers, but were mostly the Church Fathers, as well as the Latin Bible—constructed their brilliant sentences and built their arguments.

Of course, these great minds of the past did not write in English, and so the study of "grammar" could not truly be undertaken until one learned Latin. For young boys beginning instruction—usually at a nearby church under the tutelage of a priest—the first stage was learning Latin.

Latin grammar had been dissected and discussed at great length by scholars in the past, particularly by two Latin writers named Priscian and Donat. But let's save them for tomorrow.

*This work was an attempt to write a universal history, hence the name meaning "many times."

14 January 2013

"Grammar" "School"—Part 1 of 2

When we think of the history of schools, we imagine an unbroken line of buildings and teachers and groups of pupils sitting on chairs or benches or stools, and our imagination stretches back through a more and more primitive setting. That is, we think of the medieval school as visually similar to the modern classroom, but with less technology, simpler furniture, etc.

An understandable image, but not accurate.

For instance, classes at Oxford 700 years ago would not be recognizable to us. The master would probably be visiting his pupils in a room rented by them, or at his house. Furniture would not be present—no one was going to own that many chairs or stools, or even benches. They would stand together and talk.

We need to alter slightly our use of the word "school" for this context. Nowadays we use it to refer to the location or building. Just as "home is where the heart is," however, "school" was simply the gathering itself of a master and a pupil or pupils. The word school, from the Greek schola, ultimately relates back to "leisure." School (as the Greeks would say of arts in a civilization) is only possible when there is the time to cease toil and discuss higher aspirations. Early references to "school" (such as in Bede) make clear to us that it is not clear that a building is involved, just an intent to provide instruction.

Now what about "grammar"? I attended grammar school, and still use the phrase, although there was very little grammar involved. Why do we call them that? We'l look at that in Part 2.

An understandable image, but not accurate.

For instance, classes at Oxford 700 years ago would not be recognizable to us. The master would probably be visiting his pupils in a room rented by them, or at his house. Furniture would not be present—no one was going to own that many chairs or stools, or even benches. They would stand together and talk.

We need to alter slightly our use of the word "school" for this context. Nowadays we use it to refer to the location or building. Just as "home is where the heart is," however, "school" was simply the gathering itself of a master and a pupil or pupils. The word school, from the Greek schola, ultimately relates back to "leisure." School (as the Greeks would say of arts in a civilization) is only possible when there is the time to cease toil and discuss higher aspirations. Early references to "school" (such as in Bede) make clear to us that it is not clear that a building is involved, just an intent to provide instruction.

Now what about "grammar"? I attended grammar school, and still use the phrase, although there was very little grammar involved. Why do we call them that? We'l look at that in Part 2.

13 January 2013

Oswiu of Bernicia

King Oswiu (also Oswy or Oswig), who was a friend of Benedict Biscop, ruled Bernicia, a small section of Northumberland between what is now Edinburgh and Newcastle upon Tyne.

According to Bede's writings, Oswiu would have been born about 612. Unfortunately for him, his father, King Æthelfrith of Bernicia, was killed in battle against the King of the East Angles, and Oswiu and his siblings and their supporters had to flee to exile. They were not able to return to power until 633. Oswiu became king when he succeeded his brother Oswald, who died in battle in 642.

In 655, a military victory temporarily made Oswiu ruler over much of Britain. This position didn't last very long, but Oswiu still remained significant in the larger affairs of Britain. He was especially interested in and supportive of the church. Oswiu had been crucial to the foundation of Melrose Abbey. He had allowed his daughter to become a nun. His interest in relics was supported by Pope Vitalian sending him iron filings from the chains that had been used to imprison St. Peter.

In 664, the Synod of Whitby was held to make choices about how Christianity would be practiced, and Oswiu was asked to choose. He chose the version of Christianity that was being practiced by Rome over the Celtic version. This also meant calculating the date of Easter differently.

This created some awkwardness; Oswiu's son had been raised following Irish-Northumbrian practices but switched to Roman practices at the urging of St. Wilfrid (who was mentioned in a footnote here for his influence on Whitby). Oswiu chose to side with his son and Rome, but not everyone found it so easy to switch. Bede reported for 665 "that Easter was kept twice in one year, so that when the King had ended Lent and was keeping Easter, the Queen and her attendants were still fasting and keeping Palm Sunday."

The Archbishop of Canterbury, Theodore of Tarsus, traveled north to visit Oswiu in 669 and made such an impression that Oswiu was going to make a pilgrimage to Rome. He never made it, dying on 15 February 670. He was buried at Whitby, where his daughter the nun then resided.

According to Bede's writings, Oswiu would have been born about 612. Unfortunately for him, his father, King Æthelfrith of Bernicia, was killed in battle against the King of the East Angles, and Oswiu and his siblings and their supporters had to flee to exile. They were not able to return to power until 633. Oswiu became king when he succeeded his brother Oswald, who died in battle in 642.

In 655, a military victory temporarily made Oswiu ruler over much of Britain. This position didn't last very long, but Oswiu still remained significant in the larger affairs of Britain. He was especially interested in and supportive of the church. Oswiu had been crucial to the foundation of Melrose Abbey. He had allowed his daughter to become a nun. His interest in relics was supported by Pope Vitalian sending him iron filings from the chains that had been used to imprison St. Peter.

In 664, the Synod of Whitby was held to make choices about how Christianity would be practiced, and Oswiu was asked to choose. He chose the version of Christianity that was being practiced by Rome over the Celtic version. This also meant calculating the date of Easter differently.

This created some awkwardness; Oswiu's son had been raised following Irish-Northumbrian practices but switched to Roman practices at the urging of St. Wilfrid (who was mentioned in a footnote here for his influence on Whitby). Oswiu chose to side with his son and Rome, but not everyone found it so easy to switch. Bede reported for 665 "that Easter was kept twice in one year, so that when the King had ended Lent and was keeping Easter, the Queen and her attendants were still fasting and keeping Palm Sunday."

The Archbishop of Canterbury, Theodore of Tarsus, traveled north to visit Oswiu in 669 and made such an impression that Oswiu was going to make a pilgrimage to Rome. He never made it, dying on 15 February 670. He was buried at Whitby, where his daughter the nun then resided.

12 January 2013

Benedict Biscop

The cleric and writer called the Venerable Bede has cropped up many times here; his learning is known to us by his translation of parts of the Bible, his work on the Reckoning of Time, on sciences, and the respect held for him by others. Let's use him again as our lead in to another topic, with the question: "Where did he acquire his learning?" The answer is in the library at the monastery at Jarrow, built by Bede's tutor. [see the illustration]

Benedict was born into Northumbrian aristocracy about 628, and as an adult as a thegn loyal to King Oswy. About 653, Benedict agreed to travel to Rome with his friend, Wilfrid (later to be Saint Wilfrid the Elder). Although Wilfrid was detained at Lyon, Benedict continued to Rome. Already a Christian, the trip to Rome and visits to sites connected to the Apostles made Benedict more fervent than ever about his faith. So when King Oswy's son Ealfrith wanted to go to Rome some years later, Benedict happily accompanied him. This time, he did not return to England, but stopped at Lerins Abbey on what is now the French Riviera, where he undertook to learn the life of a monk.

After two years of this, he boarded a merchant ship that was heading to Rome. On his third trip there, in 668, he was given the job by Pope Vitalian to go to England and be an advisor to the Archbishop of Canterbury, Theodore of Tarsus. Returning to England, Benedict introduced the construction of stone churches with glass church windows. He also became a proponent of Roman styles of Christian ritual, rather than the Celtic style that had developed in England and Ireland.

King Ecgfrith of Northumbria gave Benedict land for a monastery in 674; Benedict would found the Abbey of St. Peter in Monkwearmouth. He traveled to the continent to bring workers and glaziers to make a worthy monastery, and made a trip to Rome in 679 in order to bring back books. Other trips were made as well to provide books for the monastery. The monastery so pleased the king that Benedict was given more land for a second monastery in Jarrow, and this was to be called St. Paul.

These were the first ecclesiastical buildings in England to be made of stone, and together they held an impressive library of several hundred volumes—also unusual for a 7th century monastery. This is where Bede had access to the learning that allowed him to write his works. One of those works was the Lives of the Holy Abbots of Wearmouth and Jarrow, in which he has this passage:

Not long after, Benedict himself was seized by a disease. [...] Benedict died of a palsy, which grew upon him for three whole years; so that when he was dead in all his lower extremities, his upper and vital members, spared to show his patience and virtue, were employed in the midst of his sufferings in giving thanks to the Author of his being, in praises to God, and exhortations to the brethren.Benedict Biscop (pronounced "bishop") died on 12 January, 690.

11 January 2013

East & West

|

| Pope Gregory at the Second Council of Lyons |

One of the items on the agenda was getting the two churches to agree to the same theology. The Filioque ["and the Son"] controversy was still an issue. The Greek text of the Nicene Creed was that the Holy Spirit proceeds "from the Father." The Roman view was that the Holy Spirit proceeds "from the Father and the Son." This divergence was firmly established in 325 by the first Nicene Council. The Greek delegation conceded to add the words "and the Son" to their version of the Creed. Sadly, Michael VIII's successor, Emperor Andronicus II (1259-1332), rejected the change.

The other East/West connection established at the Council was relations between Europe and the Mongol Empire of Abaqa Khan. A Crusade was planned, and the representatives of the Khan (one of whom went through a public baptism at Lyons) agreed to not hassle Christians during the war with Islam. Abaqa's father had once agreed to exempt Christians from taxes. Unfortunately, the Crusade never happened, and the grand gesture of cooperation did not take place.

So...improvements in East/West relations were attempted, but ultimately failed. The Council also was marred by other events. Thomas Aquinas wanted to attend, but died on the way. St. Bonaventure did attend, but died during the sessions..

10 January 2013

Gregory X

Today is the anniversary of the death of Pope Gregory X. He has already been mentioned in Daily Medieval, but let's take a closer look at his career.

His election as pope came after a three-year vacancy (1268-1271) in the position. The cardinals were split between French and Italian factions. Charles of Anjou, younger son of King Louis IX of France, had taken over Sicily and started to interfere with Italian politics. The French cardinals were fine with this; the Italian cardinals were not. The cardinals met in the town of Viterbo and vote after vote produced no clear candidate. Finally, the citizens of Viterbo locked them into the room where they met, removed the roof to expose them to the weather, and allowed them nothing but bread and water.

On the third day, they picked a pope.

Cardinal Teobaldo Visconti was Italian, but had lived most of his life in the extreme north and was unaffected by the recent Sicilian difficulties. He was chosen as a compromise candidate.

Visconti was not even aware that he was considered as a candidate; he wasn't there. He was with Edward I of England on the Ninth Crusade as a papal legate. While there, he had been met by the Polos, who had letters from Kublai Khan for the pope.

When word came to him that he was the new pope, his first act was to request aid for the Crusade. He then sailed for Italy and called the Second Council of Lyons to discuss the East-West Schism and corruption in the Church. He also heard from the Polos again, who pressed him (now that he was pope) on Khan's request for 100 priests to come east and explain Christianity. The new pope, who took the name Gregory X, could only offer a few Dominicans (who tarted out on the long journey, but lost heart and turned back).

Gregory did establish relations with the Mongols, however, when the Mongol ruler Abaqa Khan (1234 - 1282) sent a delegation to the Council of Lyons to discus military cooperation between the Mongols and Europe for a Crusade. Plans were made, money was raised, and then Gregory died on 10 January 1276. The project failed.

|

| Pope Gregory X is presented Kublai's letter by the Polos |

On the third day, they picked a pope.

Cardinal Teobaldo Visconti was Italian, but had lived most of his life in the extreme north and was unaffected by the recent Sicilian difficulties. He was chosen as a compromise candidate.

Visconti was not even aware that he was considered as a candidate; he wasn't there. He was with Edward I of England on the Ninth Crusade as a papal legate. While there, he had been met by the Polos, who had letters from Kublai Khan for the pope.

When word came to him that he was the new pope, his first act was to request aid for the Crusade. He then sailed for Italy and called the Second Council of Lyons to discuss the East-West Schism and corruption in the Church. He also heard from the Polos again, who pressed him (now that he was pope) on Khan's request for 100 priests to come east and explain Christianity. The new pope, who took the name Gregory X, could only offer a few Dominicans (who tarted out on the long journey, but lost heart and turned back).

Gregory did establish relations with the Mongols, however, when the Mongol ruler Abaqa Khan (1234 - 1282) sent a delegation to the Council of Lyons to discus military cooperation between the Mongols and Europe for a Crusade. Plans were made, money was raised, and then Gregory died on 10 January 1276. The project failed.

09 January 2013

Novatianism: Harsh Christianity

|

| Christian persecution under Emperor Decius |

Novation (also called Novatus) was a 3rd century scholar and theologian during a time when Christians were still being actively persecuted in the Roman Empire, especially during the reign of Emperor Decius (249-251). Decius assassinated Pope Fabian (c.200-250), and executed many Christians unless they chose to renounce their faith and worship the Roman pantheon. The position of pope remained vacant for a year. After the death of Decius in 251, a moderate Roman aristocrat named Cornelius was elected by a majority of local bishops.

Pope Cornelius was willing to forgive the Lapsi, the lapsed Christians who saved their lives by recanting or worshiping in the Roman style. This was unacceptable to Novatian. He got three bishops together in Rome who were willing to see things his way, and they elected him pope.

Both popes sent messengers from Rome to declare their election. Confusion reigned, then investigation. The Church in Africa supported Cornelius, as did (Saint) Dionysius of Alexandria and (Saint) Cyprian. Novatian tried to use his "authority" to create new bishops to replace those in the provinces. It quickly became clear that Corneliuus was favored over Novatian by the majority, making Novatian the second anti-pope.

The roots of his unwillingness to forgive such disloyalty to Christianity did not just come from a stern nature, however; he believed forgiveness by the Church was simply not possible. He held that only God had the power of forgiveness for sins, and that earthly prelates could not pardon the serious sin of idolatry. This was not unprecedented: Tertullian (c.160-225) had criticized pardons for adultery made by Pope Calixtus I (217-222). Ultimately, however, the church decided to allow itself to forgive sins. Novatianism survived a couple centuries after his death in 258, but as a heresy, eventually to be stamped out and replaced with a more forgiving Christianity.

Novatian may no longer have followers, but he has at least one fan, who offers a picture of Novatian's tomb.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)