On the heels of the three "Church & State" posts, it is appropriate to talk about a clash between an emperor and a pope. Today is the 936th anniversary of the lifting of the excommunication of Holy Roman Emperor Henry IV.

The roots of the conflict that led to the excommunication began in the Investiture Controversy, which can be summarized neatly: should the temporal authority of a king allow him to appoint spiritual leaders in his country, such as bishops and abbots? The practice was common, and the papacy wanted it stopped, declaring that the pope of course was the only authority who could approve spiritual appointments.

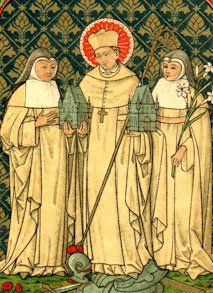

In the 11th century, Pope Gregory VII (c.1015-1085) tried to assert the papacy's right to invest bishops, but Holy Roman Emperor Henry IV (1050-1106) continued exercising the traditional practice of the kings of Germany (and other countries). The debate turned ugly when Henry called a synod of German bishops and they denounced Gregory as pope. Gregory, in turn, called a synod in spring of 1076 and excommunicated Henry, giving him one year to repent and ask forgiveness or the excommunication would become permanent.

A Christian country wanted a Christian king, and the excommunication prevented Henry from receiving the sacraments, including forgiveness for sins. This made his rule untenable, and pockets of violence against his rule broke out in Germany, ending in several German princes and prelates calling for his replacement unless the excommunication were lifted.

The 26-year-old Henry saw the difficulty of his prideful position, and offered to meet with the pope at Augsburg, in Germany. The pope agreed, but on his northward travels he began to fear that he would be putting himself into the clutches of Henry's army. On the advice of Countess Matilda of Tuscany, he repaired to the fortress of Canossa, in northern Italy, to be able to defend himself. In order to meet with the pope, then, Henry and his army had to march a further 400 miles south of Augsburg, crossing the Alps in winter. The fear that Henry would try to conquer Italy grew. Gregory gave orders that Henry was not to be allowed into the fortress.*

|

| Canossa today, with the ruins of the fortress visible |

When Henry reached Canossa in January 1077, however, he did something extraordinary. Letters written in later years by both Gregory and Henry confirm the story, if not al the details: the story says that he stood outside the gates for three days, in the snow, wearing only a hair shirt and refusing food. After three days, on 28 January, Gregory had the gates opened and Henry allowed in. Henry went onto his knees before the pope and begged his forgiveness. The excommunication was lifted. All was well.

...or was it?

Henry was once again a Christian in good standing, but Gregory refused to endorse his return to the throne of the Holy Roman Empire. Two months after his stand at Canossa, a group of German aristocrats and archbishops and bishops declared his brother-in-law Duke Rudolph of Swabia. Years later, the Protestant Reformation would see Henry as a champion of the rights of Christians against an oppressive and wayward Roman Catholic Church, but right now, the troubles were just beginning.

But that's a story for another day.

*The illustration is n 1856 woodcut made from a painting by Oscar Pletsch (1830-1888), showing Henry IV outside Canossa

.jpg)