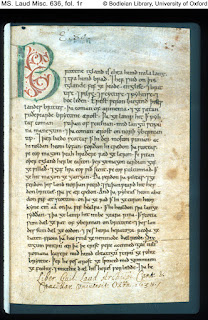

Rabbi Levi ben Gerson, also known as Gersonides, lived from 1288-c.1344. He was from a family of scholars: his father, Gerson ben Solomon of Arles, was the author of the

Sha'ar ha-Shamayim, an encyclopedia of natural science, astronomy, and metaphysics.* Levi is credited with first mentioning, and possibility inventing,

Jacob's Staff. (He references Genesis 32:10 when he describes the device; this is likely the origin of the name.)

At a time when religion, philosophy, astronomy, astrology and science were overlapping (and in some cases, interchangeable), Gersonides' greatest work, which was philosophical, contained his greatest contribution to astronomy. He put twelve years (1317-28) of effort into the

Milhamot Adonai ("Wars of the Lord"), whose six books dealt with 1) the soul, 2) prophecy, 3) & 4) god's knowledge of facts and providence, 5) astronomy/astrology, and 6) creation and miracles. Gersonides firmly accepted astrology and the celestial hierarchy of powers inherited from neo-Platonists and pseudo-Dionysius (far too complex to go into here), but he also brought mathematics and observation to his work with extraordinary results for the time.

|

| Postage stamp honoring Gersonides. |

Gersonides rejected the Ptolemaic system of epicycles to explain the erratic motion of planets affixed to their crystal spheres surrounding the Earth. According to Ptolemy, epicycles explained the changing size of planets; he said, however, that Mars varies by a factor of six; Gersonides' observations told him that Mars's apparent size varies only two-fold. Gersonides used the Jacob Staff and a

camera obscura (pinhole camera) to make careful observations over several years. For Gersonides, 48 crystalline spheres were needed to explain the apparent motion of various heavenly bodies. This expansion of the "physics" of the Ptolemaic model was nothing, however, compared to the actual physical expansion he proposed.

Careful observation with the Jacob Staff, the

camera obscura, and math made Gersonides declare heavenly objects to be much farther away than previously calculated. Ptolemy claimed the distance to Venus was 1079 Earth radii; Gersonides estimated it to be 8,971,112 Earth radii away. Ptolemy said the fixed stars were 20,000 Earth radii away; Gersonides estimated them to be at a distance 10 billion times greater.

Pope Clement VI had the "Wars of the Lord" translated into Latin in 1344, making it available to the west. Its impact was minimal, however; we know of a few scholars who were influenced by it, and Kepler asked a friend to send him a copy in the 17th century. But it took Copernicus two centuries later to "confirm" to Western civilization's satisfaction that Gersonides was on the right track.

*

As I have mentioned about medieval encyclopediæ before, they were often compilations of previous works; this one drew from Claudius Ptolemy's Almagest and the Morah Nebukim, or "Guide for the Perplexed" of Maimonides. A 1547 edition of ben Solomon's work can be had from Kestenbaum & Company.

.jpg)