Until the beginning of the fourth century historiography remained a pagan science. With the exception of the Acts of the Apostles and its apocryphal imitations, no sort of attempt had been made to record even the annals of the Christian Church. [Philip Schaff, Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers]

The situation described above changed with Eusebius of Cæsarea (c.263-339), first mentioned about the finding of the True Cross. Eusebius decided to write a history of the Church from its start to his time, earning him the title "Father of Church History." He did such a commendable job that none of his contemporaries bothered duplicating his work. There were, however, attempts to continue it, which brings us to Socrates Scholasticus.

Socrates Scholasticus, also called Socrates of Constantinople because he lived there and was very proud of his city, leaves us very little biographical material to go on. His continuation of Eusebius ends in 439, which is presumably the date of his death. We can only guess at his birth, and then only if we make assumptions about whether he was an eye witness to any of the events about which he writes.

But we can tell a few things about him. He was very proud of his city, Constantinople, praising it and describing changes to it. Although he holds bishops in high esteem for their position and monks for their piety, he is able to criticize prelates and decisions without hyperbole.

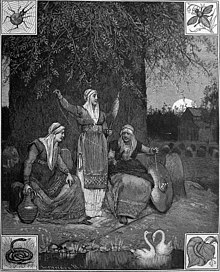

Also, as much as he clearly is devout about the Church, he gives details of offshoots without condemnation. Therefore, he writes simply and without hostility about Arianism and the divergent practices of Macedonians, Eunomians, and others who were considered heretics. Socrates' desire to be complete with his history makes him one of the prime sources for updates on a 3rd-century schism first mentioned by Eusebius. In fact, he offers so much detail on Novationism that some scholars think he was a Novationist himself. What was a Novationist? A follower of Novation, one of the first people to deliberately set himself up as an anti-pope.

But that's a story for another day.