Henry's involvement—deliberate or not—in the murder tarnished his reputation; the death of Becket was one of the points brought against him during a rebellion in 1173. But let's focus on the immediate events after 29 December 1170.

The four knights responsible fled northward, to the castle of one of their number, Hugh de Moreville. Regardless of their "good intentions"—they thought they were carrying out orders of a king—the murder of an archbishop was not going to be without consequence. They might have thought to get to Scotland, where English law would not follow them. The four were excommunicated by Pope Alexander III. They were not in immediate danger of secular punishment: Henry did not confiscate their lands, which would have been appropriate for the circumstances. When they appealed to him for advice on their future in August 1171, however, he refused to help them. They ultimately went to Rome to seek forgiveness from the Pope, whose penance for them was to go to the Holy Land and support the Crusading efforts.

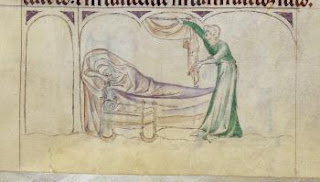

Back to Canterbury and 29 December 1170: the monks began to prepare the body for burial. Legend says they were astounded to find that he wore a hair shirt under his clothing: a sign of great piety, to willingly do penance through discomfort. His coffin was placed beneath the floor of the cathedral, with a hole in the stone floor where pilgrims could stick their heads in and kiss the tomb. The martyr's tomb became an enormously popular pilgrimage site; from martyr to saint took only two years: he was canonized by Alexander III on 21 February 1173.

Fifty years after his death, his bones were put into a shrine of gold and jewels—affordable because of the radical increase in donations and offerings due to the popularity of St. Thomas of Canterbury—and given a more prominent place behind the high altar. Sadly, the shrine and bones were destroyed by Henry VIII in 1538, and all mentions of Becket's name were to be eliminated. Despite Henry's efforts, Thomas Becket is still one of the most popular and best-known martyrs and saints in English history.

As was typical for prominent figures, especially saints, several legends cropped up about him with no evidence, but several locales tried to connect themselves to a now-famous figure. I'll share some of the more outrageous stories next.